Violence to the fourth power…

Author: Karl Jacoby

Converting history into words is problematic. History is countless simultaneous events tangled up in each other, while most storytelling tends to be linear. In the traditional approach, the historian gathers a pile of interrelated facts and attempts to assemble them into a coherent story, usually arranging them along a linear timeline. But if an author is brave enough he or she might try something different. In Shadows at Dawn, historian Karl Jacoby, approaches one of the most notorious events in western US history by presenting four completely different – and almost incompatible – perspectives. It’s a success in so many ways.

Converting history into words is problematic. History is countless simultaneous events tangled up in each other, while most storytelling tends to be linear. In the traditional approach, the historian gathers a pile of interrelated facts and attempts to assemble them into a coherent story, usually arranging them along a linear timeline. But if an author is brave enough he or she might try something different. In Shadows at Dawn, historian Karl Jacoby, approaches one of the most notorious events in western US history by presenting four completely different – and almost incompatible – perspectives. It’s a success in so many ways.

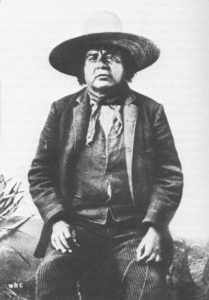

The entire book centers on a single morning in April 1871 in the picturesque Aravaipa Canyon, about 120 miles southeast of what is now Phoenix, Arizona. In the predawn hours an assemblage of American, Mexican and Tohono O’odham men gathered, watching over a sleeping encampment of Nṉēē people (known by outsiders as the Western Apache). They proceeded to try and kill every single one of them – mostly women and children – clubbing them to death or shooting them as they tried to run for cover. By the time the dust had settled, they had killed more than 100 people. The couple dozen children they didn’t kill were gathered up and sold into slavery. The atrocity would soon be called the Camp Grant Massacre and news of it quickly spread from coast to coast. None of the participants were ever convicted of any crime.

The obvious approach would be to tell the story from the perspective of the victims. They certainly are the most deserving and the least likely to have a voice – given that they’re dead. But Jacoby is cleverer than that. Recognizing that the history of the American West is much more complicated than we often like to acknowledge, he tells four different interrelated stories, producing a much more interesting chronicle in the process.

Organizing the book with a brilliant simplicity, he presents a chapter about each of the four different peoples – Tohono O’odham, Mexican, American and Nṉēē – before the massacre, then presents four more chapters exploring the aftermath. Each of the eight chapters is told from the unique perspective that different peoples brought to the harsh Arizona borderlands. Going back centuries, Jacoby deftly uncovers the countless irreconcilable historical and cultural differences that existed between the different actors, explaining how these differences made the area so endlessly violent. He also attempts to understand each perspective on its own terms, but at the same time he doesn’t try and defend the indefensible, calling out hypocrisy and injustice as it surfaces time and again.

In the epilogue, Jacoby presents the idea of the palimpsest. It’s a great word – that I always have to look up on those rare occasions when I come across it – and it’s a particularly intriguing approach to history. An ancient manuscript that has been used repeatedly, leaving layers of sometimes legible text one over the other, the palimpsest is a great metaphor for what the author is trying to achieve in Shadows at Dawn. He’s carefully constructed each layer and then laid it over the others, although each layer may not always be entirely legible in the context of its neighbors. In the process he’s created a remarkably complicated historical chronicle and meditation on violence that is everything great history writing should be: passionate, eye opening and intriguing.

— D. Driftless

Check out some other reviews of books that look at the history of the Arizona borderlands: Trace / Blood and Thunder / Blood Meridian

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”0143116215″]

- Best Non-Fiction of 2016 - February 1, 2017

- Little Free Library Series — Savannah - May 22, 2015

- Little Free Library Series — Wyoming - November 30, 2014