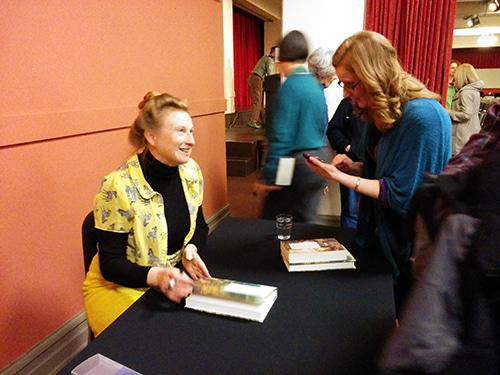

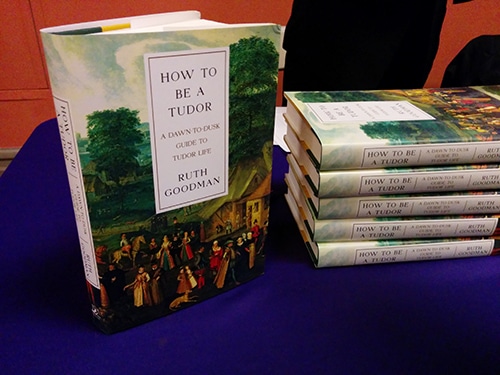

What does a 21st-century person need to know about how to be a Tudor? When people think about life in Tudor-era England (basically the 16th century), they often imagine the extremes — either the glittering wealth and lavish courts of King Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth I, or a miserable medieval peasant’s grim existence. But, as historian Ruth Goodman explains in her new book How To Be a Tudor, there were many people in between. Farmers owned land and raised animals, skilled tradesmen made beautiful and high-quality handmade goods, and the monasteries offered employment, community, and social welfare. And Goodman should know — she spent a year living the Tudor life, along with two other historians, to film the BBC series “Tudor Monastery Farm.” I got a chance to see Ruth Goodman in Seattle recently, talking about her time-traveling experience and dispelling some popular Tudor myths.

Myth: Everyone was filthy and never, ever bathed

TV shows like “Tudors” or “Wolf Hall” (which Goodman served as a consultant on) go all-out with the stunning velvet gowns, elaborate braided hair, and over-the-top jewels for both men and women. (You can even buy replica jewelry made to look like the pieces worn on those historical dramas.) But we often assume that as beautiful as they looked, people back then stank to high heaven because they didn’t bathe.

Well, it’s true that Tudor people didn’t hop in a tub and lather up. They believed that disease floated around in the air as a “miasma” and opening up your pores by scrubbing and soaking in hot water put you at risk of getting sick. But that doesn’t mean they were filthy. People would wash their hands and faces every day, and rubbed their bodies briskly with a cloth to exfoliate and clean the skin. Those fancy velvet gowns couldn’t easily be washed, so they changed their linen underclothes frequently (once a day or more), allowing the underclothes to absorb sweat and odors. For oral hygiene, people would rinse their mouths out, wipe their teeth with a cloth, remove food particles with toothpicks, or chew on herbs to freshen the breath. Goodman says she tried Tudor-style hygiene herself during the show and nobody noticed a thing!

Myth: The food was awful and people used spices to cover the smell of rotting meat

Goodman says that the food of the Tudor era was actually quite delicious, and people’s diets were seasonal and varied. Bread and ale were served at every meal for working-class folk, and a meat and vegetable “pottage” would be simmering on the fire, supplemented with whatever odds and ends were on hand. Fish and eel were a treat, pork and other game would be salted and preserved for winter, and the well-to-do ate roast geese and swans at feasts. But people wouldn’t have wasted precious spices like cinnamon, nutmeg, or cloves on rotting meat — they were simply too expensive and rare to throw away on spoiled food.

Another surprise is how many dietary staples we take for granted that Tudor-era England didn’t have: potatoes, corn, coffee, or tea, just to name a few. Those all came from other countries and weren’t grown or easily imported back then.

Myth: Women had no rights or power

Even though England, Scotland, and Spain had reigning queens in the 16th century, it’s a common misconception that women had few rights or privileges back then. In fact, Goodman says, Tudors valued expertise and skill in both men and women — which is good, because there was a lot of work to be done!

In addition to cooking and cleaning, women were responsible for baking bread and brewing beer, preserving fruits and vegetables, curing meat, making soap and candles, spinning wool and linen, and growing vegetables and herbs. Everything dairy-related was seen as women’s work, so women usually tended and milked the cows, as well as churning butter and making cheese. Milkmaids earned more than other types of servants, so it was a desirable job to have. Some housewives became quite well-known for their cheesemaking, and they generally kept the money they earned from their dairy products — a valuable form of financial independence.

Upper-class and noblewomen were expected to run their households or estates in their husband’s absence, so they had to know how to manage the accounts and bookkeeping, oversee supplies and maintenance, and represent the family. A young upper-class woman might also be sent to the royal court as a lady-in-waiting, or to serve another noblewoman, and it was her responsibility to help advance her family by networking, winning royal favor (which could result in valuable gifts or lucrative titles and positions), and marrying well.

Working-class women who weren’t managing a household could pursue careers as street vendors, bakers, milliners, tailors, brewery workers, textile workers, servants or seamstresses.

You can watch Tudor Monastery Farm online to get a look at everyday life for working-class farmers in Tudor times. And don’t forget to check out Ruth Goodman’s book, How To Be a Tudor!

Sign up for our newsletter and get more awesome book lists in your inbox.

You might also like:

- Spring 2020 Book Preview - May 15, 2020

- Winter 2020 Book Preview - January 1, 2020

- Fall 2019 Book Preview - September 26, 2019

Leave A Comment