A Fallen Nun, a Courtroom, and a Secret in Plain Sight

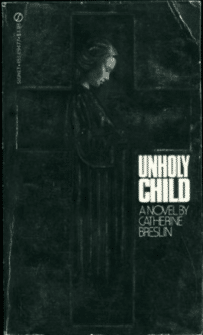

Author: Catherine Breslin

Unholy Child’s back cover blurb promises something taboo – sinister secrets erupting behind convent walls boiling over with hints of Satanism and Rosemary’s Baby. At least, when I first read the crumpling back cover, that’s what I expected. The real story, however, is something deeper, looking beyond horror into the soul of its characters and the motivations behind shame. The author has a point – one that will catch many readers who were ready for a late night B-movie vibe off-guard.

It starts when Sister Angel Flynn, a self-proclaimed virgin and beloved schoolteacher, is discovered in a pool of blood that stretches from the convent’s shared bathroom to the sister’s modest room. Her fellow sisters don’t know what to think – attack, medical issue, something worse that they have seen all along but steadily, righteously, ignored?

When the adamant doctor, a Catholic who has issues with the disclosure, reveals that Sister Angela has passed a placenta, questions arise: where is the baby and how could a cloistered nun transgress beyond the strictures of the church? Moreover – how did nine months go by without anyone noticing, without anyone saying anything, without anyone helping?

When the baby is found, the story and the questions get darker. As a lengthy trial puts the sisters in the spotlight, it soon becomes obvious, at least to jaded journalist Meg Gavin, that society is too caught up on the idea of sex and its shameful forbidden nature and not on what really happened to that baby and to the young woman who couldn’t dare ask for help. While the world wants to be hush-hush, Meg wants to know what happened behind those closed doors and blow the case wide open, perhaps releasing some inner demons from her own cloistered childhood. Other forces, however, are subtly maneuvering a cover-up, and not for the reason you think.

Catherine Breslin’s dauntingly sized novel isn’t horror per say, but more akin to a Jodi Picoult novel, complete with a final focus on a trial and the shifting chapters that give us a frank, sometimes unappetizing, look into the minds of the many characters. Other reviews have declared Unholy Child as an attack on the Catholic Church. There is a certain aspect of that, all interwoven with Catholic guilt and the horrifying idea that if nuns and priests can fall from grace so hard (when it is evidently their sole duty to live as an icon) then religion has no place and, even more devastatingly, no lasting meaning. These ideas, however, are more accurately represented as fears, the confusion of doubt in an imperfect world.

Catherine Breslin’s dauntingly sized novel isn’t horror per say, but more akin to a Jodi Picoult novel, complete with a final focus on a trial and the shifting chapters that give us a frank, sometimes unappetizing, look into the minds of the many characters. Other reviews have declared Unholy Child as an attack on the Catholic Church. There is a certain aspect of that, all interwoven with Catholic guilt and the horrifying idea that if nuns and priests can fall from grace so hard (when it is evidently their sole duty to live as an icon) then religion has no place and, even more devastatingly, no lasting meaning. These ideas, however, are more accurately represented as fears, the confusion of doubt in an imperfect world.

Meg Gavin, our staunchly brazen, atheistic journalist is more an anti-hero. Yes, she cares on some level about the nun; on other even deeper levels about the baby (her research with an abortionist is utterly grisly and thought provoking), but she is hardly a liberated paragon. Unable to keep a relationship and deeply jaded to the point that sex has become her weapon, Meg is hardly a figure you like. Indeed, she is almost as frustrating as the silent, goody-two shoes Sister Angela who swears, in child-like innocence, that she remembers nothing of the child or of what she did to him.

In a way, this book reminded me of the movie Doubt. It’s not easy on the church. It’s not easy on those outside of the church either. It’s about doubt and fear. It’s about not wanting to see – the old adage of see no evil, hear no evil, etc. In the end, it probably does more harm than good, yet the story has an intriguing way of sinking in a slowly reeled hook that is somehow mesmerizing. You probably will finish it without knowing quite what to think and of whom. For this book, there are no tidy answers.

Finally, may characters and many pages later, you have a theory, more or less confirmed. Sister Angela’s snatches of lost memory come full circle and you know what is really happening and, most likely, how it will ultimately end for her. And yet, for the novel’s odd sleeper allure, its quiet horror, the ending is abrupt and unsatisfying, the story folding from the weight it has established. Breslin has asked some dizzying questions, examining everything from personal shame to the weight of religion and the reverse weight of a lost society trying to replace it. But there isn’t an answer – not that we expected one. We know, or think we do, what happened to the baby, what took place between the discrepancy of Angela’s testimony and the events others described. It’s the fact that we did expect a better farewell from Sister Angela though, something less rushed, richer, more haunting, that leaves us feeling short changed. In the end, Breslin’s novel still finds what it seeks; it stirs life, failure, fear, sickness, shame, religion, society, justice, into one simmering cauldron and then asks – what does all of this make?

- Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews/

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”0451094778″]

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019