“Can I be everything and nothing at the same time?”

“Can I be everything and nothing at the same time?”

Author: Trang Thanh Tran

In the post-apocalyptic town of Mercy, Louisiana, the red algae blooms across the water like blood, and strange, mutant creatures frolic in the ocean. Few residents remain. Those who do are haunted and desperate.

Enter Noon and her mother, who trawl for the Lovecraftian sea life, making a living by bringing their finds to the corrupt harbormaster. Noon is lost in memories of what happened that night on Chelsea’s Beach. She’s been lost longer in the shadow of her brother. She was never the son. Never the wanted one. And now with brother and father dead, she’s all her mom has left. But she’s not enough. Her mom is convinced that the men in her life are being reincarnated in the strange sea creatures, and she is determined to protect them, despite the ultimatum of the harbormaster. Noon, however, will do anything to survive.

And so the ultimate hunt begins. Noon, teamed with the harbormaster’s knife-wielding daughter, Covey, follows local legends to suss out a human-like monster that destroyed the scientists investigating the bloom. What they find, however, is transformation and transition, resulting in a showdown that questions the monstrousness of humanity and the unknown in us all.

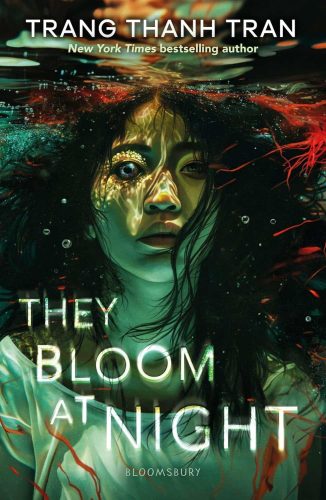

First, They Bloom at Night has an incredible, haunting cover. The lyricism of this YA horror starts off strong, creating Lovecraft and Twilight Zone vibes. Noon’s haunting also brings the spooky darkness and makes us connect with her. We feel that she has never been wanted. We also understand, implicitly, that the one time she was wanted, she was violated.

But then, the roiling sea calms, and we are left in the stagnate doldrums. We get a lot of imagery, a lot of vibes, but very little actual action. The surrealism isn’t enough to hold up the tale, and soon we want to see something, have the story progress. Vibes are good and all, but where are the monsters?

Noon and Covey, who form an uneasy alliance that obviously belies an undertow of attraction, start to investigate what the scientists were researching, and in the unlikely nature of all YA books, they seem to understand the secrets behind the research immediately. Because . . . of course a 17-year-old would be able to look at a few pages, a few scrapes of left behind paper, and one escaped octopus and just understand exactly what is going on, what the red algae is, and what it is doing. There must have been a better way to deliver answers. A more realistic way. Heck, even a convenient journal turning up would have helped.

Then, we get a blast from the past when a long-lost friend, never mentioned, shows up on scene and gives Noon and Covey shelter and further answers. It’s too effortless, too easy. The surreal has caved and now we are left with the dues ex machina floundering of a novel that was all based on vibes but has little actual substance. People turn up at key moments, information is delivered as needed, and soon the author transcribes the horror into heavy-handed metaphor about gender-identity and fluidity. Again, where are my monsters? Where’s my carnage? Where is my spookiness?

At the end, we get a transition that, of course, allows the foreseen revenge ending and furthers the preachy nature of a narrative that has shifted out of story-telling mode to straight out preaching.

For example, we get this quote that is used, again and again, and over explained (in case we didn’t get it.) “Monsterhood is a girl’s body you don’t belong in.” We also get the less than subtle “the future is trans.” Interestingly, though, despite the overt themes of nonbinary gender identity and trans rights (Noon switches between wanting to be nonbinary and wanting to be male), the author never addresses the subject introduced in the beginning: Noon wanted to be a boy not because she felt like one, but because her family did not value girls, and even after her brother’s and father’s death, her mother valued her less. Why did we NEVER talk about this more, but make her transition seem like a good thing, instead of a response to really, really bad parenting and life-long trauma? Are we saying that her transition to a man, then, edified the idea that women are meaningless, and to gain meaning and value to her family, she must shed the feminine and become the masculine? Isn’t that just saying her family’s bias was right? And just to be clear, no I don’t think the author was saying this . . . but that’s what the narrative ended up saying by abnegating the complexity of the moment and just going for the pat “yay, she found herself in the apocalypse” moment. That’s the problem with writing to make a point instead of writing a story.

In the end, we get a weird happily ever after that just does not fit those sweet, sweet disturbing horror vibes. The story itself has transitioned from a “oh yeah, I’m going to so have nightmares after reading this one,” to a “oh, yeah, the author had a point and made it” moment. The storytelling stops when the preaching starts, but in all honesty, the slow pace had killed the magic before.

This one had so much potential, but ultimately They Bloom At Night had more idea merit and lovely moments of lyrical quotes than it had actual content and heft. I think this story could be well told (loved the folklore mixed with the imagery), but it ultimately was sloppy and undisciplined. Not recommended.

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019