The True Story of Elisabeth Fritzl

Author: John Glatt

I came to the true story of Elisabeth Fritzl, an 18-year-old Austrian woman who was raped and imprisoned in a secret cellar for twenty-four years by her own father, through Bailey Sarian’s Murder, Mystery, and Makeup podcast. I was in equal parts shocked and horrified – both by the crime itself and the fact that no one else in the house, including Elisabeth’s mother, siblings, and over 100 boarders over two decades ever noticed anything strange.

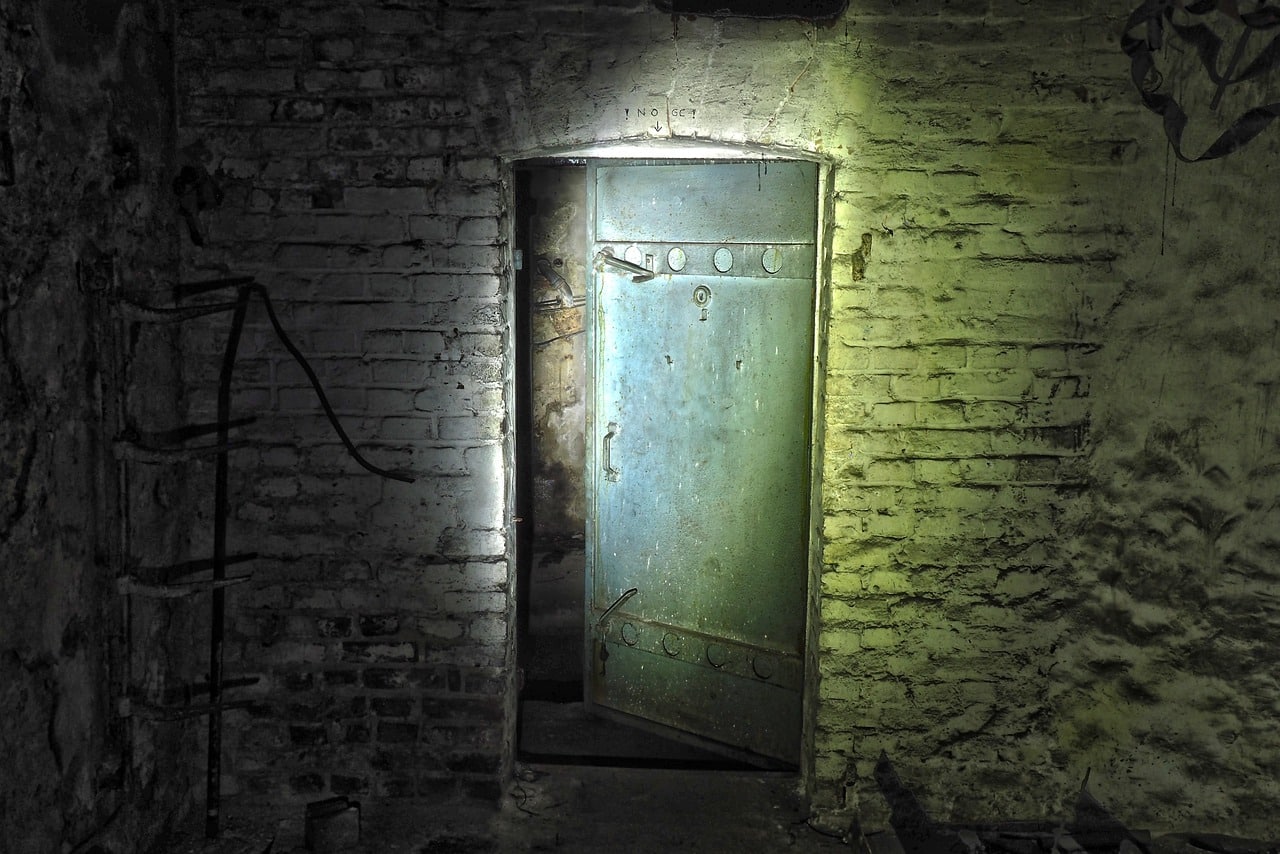

Elisabeth’s father and captor, Josef Fritzl, spent years building the secret cellar, moving tons of rock and constructing an elaborate, technologically sophisticated prison in his own house. How did no one notice? How did no one comment on his stringent rules – the forbidden nature of the basement, the late-night runs where he was seen taking wheelbarrows of groceries into the cellar, and Elisabeth’s supposed “letters” home. How did no one investigate? How did a man with prior convictions for sexual assault fly-under the police’s radar? Seeking further answers in the age-old question of how do monsters-become-monsters and why does no one stop them during the very clear early warning signs, I finished Bailey’s immersive episode and immediately picked up John Glatt’s Secrets in the Cellar.

Glatt had a sensational topic, so it’s easy to get and keep our interest early on. He mostly goes chronologically, after an introductory chapter that captures the cramped nature of the tiny, nearly airless cellar and the desperate circumstances that finally lead to Elisabeth’s re-emergence into the world. I’m starting to notice a theme in my recent true crime addiction: there are always signs. Josef was definitely strange long before he began plotting his daughter’s imprisonment and what ended up being his family below the stairs (Elisabeth bore seven children from her own father during this time). Rosemarie, Josef’s wife, even knew about his rape conviction of a fourteen-year-old, which occurred during their marriage. Josef was likewise known to have a voracious and violent sexual appetite, visiting local brothels and making yearly pilgrimage to Amsterdam where many of the local sex workers refused to take him as a client, fearing for their own safety. Yet, despite his clearly criminal behavior and numerous rape convictions, Fritzel was considered an upstanding citizen.

He began raping Elisabeth early in her life, and some of her friends even remark on how she finally told them, sharing her trauma. She ran away from home multiple times. She showed signs of being disturbed by her constant abuse. Yet no one did anything.

When she disappeared, Fritzl spun a story that she joined a cult. It was accepted and never investigated. When Fritzl learned that taking in foster children brought money, he began orchestrating Elisabeth’s cellar born children showing up on the doorstep, a note from her in hand: the cult didn’t allow children. Again, no questions, no investigations. While many of Fritzl’s boarders thought that the time he spent in his cellar was downright odd, and some of them claimed to hear noises, including a woman in distress, nothing was done. No one investigated.

When she disappeared, Fritzl spun a story that she joined a cult. It was accepted and never investigated. When Fritzl learned that taking in foster children brought money, he began orchestrating Elisabeth’s cellar born children showing up on the doorstep, a note from her in hand: the cult didn’t allow children. Again, no questions, no investigations. While many of Fritzl’s boarders thought that the time he spent in his cellar was downright odd, and some of them claimed to hear noises, including a woman in distress, nothing was done. No one investigated.

The elaborate crime continued as Fritzl became older and his family below stairs grew weaker. Glatt weaves the true crime narrative together in an almost storybook fashion, painting both the sordid nature of Elisabeth’s subjugated life and the unhealthy nature of the damp, closed off basement. Fritzl’s children were unable to fully stand up in the basement, and eventually health concerns lead him to release Elisabeth to take her grown daughter, now dying, to the hospital. That is when the story broke, and Glatt opines that it was because Fritzl realized he was simply too old to handle the situation anymore and the family below stairs.

From there, the story shifts to the trial, although it was finished and published before the outcome, which makes this book irritatingly incomplete. We also spend time watching the family below stairs meet the family above stairs, and the therapists work to merge the two families together. We see the trauma of the below stairs children encountering nature, sunshine, and other people for the first time, yet the door here also closes prematurely. We get the sense that everyone will survive, but remain forever haunted (PTSD for sure), but there are lingering questions, including how (and if) the relationship with Rosemarie and Elisabeth can be repaired.

Fritzl himself seems oddly emotionless: neither expressing remorse nor even fear. We don’t get a look into his psychology or any true explanations for the crime, beyond his own claim that Elisabeth reminded him of his own mother and their unhealthy relationship. There is no proof, no real time spent with psychologists discussing what drove Fritzl to live such a double life. Instead, Secrets in the Cellar is more focused on what happened and how Elisabeth and her children survived and started to re-integrate into the world. It was very well written and powerfully articulated. We saw and felt alongside these people, but it all ended too soon, the rush to publication keeping us from getting Fritzl’s conviction (which you can see in this article) and what ultimately happened to the two families, coming together as one.

Nevertheless, Secrets in the Cellar is a gripping true-crime narrative that also serves as an unintentional call to action. We should not brush off the strange around us – we should act. If just one of those boarders had said something, some of the tragedy and agony could have been spared. It also makes us wonder how many seemingly ordinary homes hide dark secrets and calls us to pay better attention, to try and help one another, and to suspect even the “upstanding,” because often that is a mirage not based on facts.

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019