Mercy Vs Law, Society Vs Humanity

Author: Victor Hugo

Les Miserables has long been a staple of our shared narrative – an epic story of heroism and villainy and all the shades of desperation and hopelessness that lie in between. Spawning numerous plays and movies, as well as countless adaptations and abridgements, Hugo’s story survives not because of its perfection but because of its uncompromising power.

I first encountered Les Miserables as a child right on the cusp of adulthood, although I was ultimately more inclined to childish things than the new world opening up to me. I saw Hugo’s story represented in a movie, which stayed mostly true to the overarching story; fifteen odd years later, I still remember the closing scene, the gut wrenching desire to cry, and the commentary on a “justice system” turned intolerably cruel. I’ve been promising myself to read the book ever since, but its sheer volume (1,000+ pages) and my first experience with Hugo (the slog through the digression that is known as Hunchback of Notre Dame, which is entirely more about the architecture of Notre Dame than the fate of the hunchback) kept me from approaching the task until now.

Ultimately, I’m glad that I took this long journey. It was an unforgettable foray into the depths of humanity at both its most angelic and most depraved. Hugo, however, remains a difficult author, not so much for his writing style (it’s languid and beautiful) but for his affinity to add non-fictional essays wherever possible, stilting what is a dynamic plot. But more on that later.

For those not in the know, Les Miserables follows the life of a man, Jean Valjean. Caught as a young man, stealing a loaf of bread to keep his sister and her needy children alive, Valjean was sentenced to 19 years of imprisonment and hard labor. As his body grew more stolid and strong, his soul collapsed within him. He emerges, having paid his supposed debt to society, but even still that is not enough. His sister and her children are gone, presumably long dead or else captured into prostitution, and Valjean, with his tell-tale convict papers, is not wanted anywhere in society. The bitterness is extreme and heartfelt and sets him on a dark path that is intercepted by a kindly Bishop who through one true act of kindness and forgiveness alters everything for Valjean and allows him to start over. But, secrets will out and Javert, the ineffable police inspector, is determined to capture the convict again.

As Valjean makes his journey through society, now hidden behind a secret name, success is offset by compassion. But nothing is so clear-cut in Hugo’s world, and the “justice” system is far from done. Javert is not the only antagonist, and soon circumstances put Valjean in a difficult position.

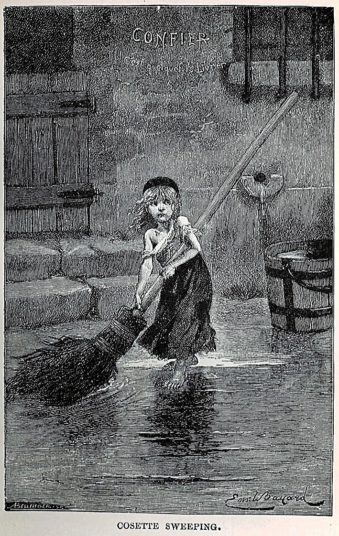

Meanwhile, Fatine, a young woman destroyed by the love of a man, is left pregnant, unmarried, and desperate. As she slowly works her way down in society, desperate to do anything to take care of her child, Cosette, destiny is set in motion. As Fatine sells first her hair, then her teeth, and finally her body, her path intersects with Valjean, and what’s right and what’s wrong takes them all far outside of the law and its steadfast interpretation by Javert.

As Les Miserables continues, other characters come and go. Dregs from the bottom of society, criminals, orphaned street children, policemen, and a wealthy young man consumed by monarchism and an ancient debt that will soon get him entangled in the mess of all the miserable people around him. It culminates in the June rebellion of 1832 where history and fate interweave, love and romance meet despair and war, idealism and reality clash, and the meaning of duty leads to shattering decisions.

Les Miserables ranges over a lifetime with Valjean starting as one type of person and then working his way through an incredible character arc, which pits his own delusion of his criminality against the necessity to thwart the law and protect the neglected and the brutalized. Valjean’s encounter with Fatine and her dying wish that he protect her daughter, held by a ruthless foster family, forces Valjean to take a strange path and find his own form of justice, his own definition of what’s right against what is legal. This is where the crux of the novel lies and where Hugo shines his brightest. The law is dogmatic whereas love and God are not. Human law is pitiless, but God’s law sees room for forgiveness and understanding. One thwarts and plays against the other, and simple interpretations are thrown aside as we submerge ourselves into the underworld of Paris and watch good intentions lead to criminal actions, lead to desperation, which then leads ultimately towards violence and a weird sort of connection. The world of the street is a dark place, but by our complacence have we not made it so? Have we not determined that once fallen escape and retribution are impossible?

The story lives up to its title. It’s a tear jerker and while some characters elicit more sympathy than others (I was so mad at Cosette and Marius by the end) Jean Valjean ties us emotionally to the narrative, even through Hugo’s sermonizing about everything ranging from the ultimate historical meaning of Waterloo to the creation of Paris sewers and a surprisingly long narrative on human waste and its existential meaning. If you can read through this tale and not cry – not feel for Jean Valjean as though he is a close and much abused friend – then you ultimately have no soul and no love for humanity. Hugo is a master at character and a master at revealing injustice in all its fetid ugliness.

What he is not a master of, however, is pacing. While the story is itself is sheer perfection, the delivery hurts the narrative and its forceful point. Hugo likes to ramble. A LOT. Because of this, I often found myself picking up the book, not for the joy of reading or the revelation of Hugo’s complex morality, but out of duty. This is a pure Hugo issue, and he is the only author to ever make me feel kindly towards abridging. Every time the narrative starts to build power and the theme force, Hugo stops and goes on (sometimes for hundreds of pages) about things that simply don’t matter to the story. This devalues everything he is working toward. As Valjean finds himself transforming into a father for Cosette and finally finding love among people, everything stops for pages and pages as we deep-dive on monasticism, specifically its merits and cultural implications as opposed to its unnecessary strictures and flaws. An interesting topic, sure, but does it belong here? The answer, as always, is no.

Hugo likes to set his stage with history, and I am surprised that he doesn’t just go back to the beginning of time. Any mention of a road, a building, a personage, leads to a back-in-time extravaganza with much eulogizing of everything from military tactics to the virtues and vices of Napoleon (long dead by the time this story starts, I might add.) It’s enervating and saps the joy of reading out of a narrative that is, in and of itself, unforgettable and unsurpassed. Just why, Hugo, why?

In the end, despite Hugo’s rants (oh, there are so, so many and they are soooo long) Les Miserables is so amazing that it’s worth the trouble, even (if you can stand it) the non-abridged version. Ignore the asides and keep your eyes on Valjean, on Javert, on Cosette, and allow your heart and connection to prevail during the dry moments. Valjean is an unforgettable character. He will leave you in tears, but ultimately his story will change your life and perception, will make you kinder and more empathetic, will make you look at the why behind people’s circumstances instead of relying on knee-jerk judgment, and will make you accept (and hope to change) your complicity in the entire mess of society and despair.

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”1977076602″]

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019