A So-So Vignette Into Tracking Child Predators

A So-So Vignette Into Tracking Child Predators

Author: Jeffrey L. Rinek

Jeff Rinek always wanted to be part of the FBI, even as a child. To him it was a real way to get involved, to be a hero, to help people. He thrived on FBI stories growing up. But it didn’t look like it was ever meant to be. For one thing, Jeff was Jewish, and in the 70s the FBI was mostly comprised of white Christians. Not a place for a Jewish man, especially one with physical disabilities. Passing the physical tests alone was a nearly insurmountable challenge. But entering a culture set against him? A pipedream, to be sure.

Except, Rinek never accepted no for an answer, and through perseverance and skill he made his dream come true. That’s when his talent for eliciting confessions, for seeing the perpetrator not as a monster but as a fellow human in need of empathy set him on a course to track down child molesters.

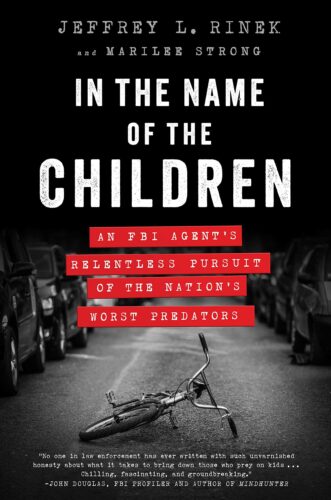

In The Name of The Children is Rinek’s story of joining the FBI, of tracking down and putting away several notorious criminals during his 30-year career. In this book, he shares the stories that have stayed with him and haunted him. In the conclusion, he also gives us a brief look into the aftereffects of such a dark career on his mental and physical health.

Rinek’s best story is that of Cary Stayner, a murderer and a pedophile who was responsible for the Yosemite Park Murders. Stayner did not start as an evil man. Rinek had personal insight into his story, and thought that despite the man’s cold-blooded nature, he was not a psychopath. The accidental connection Rineky made with Stayner and the subsequent confession is a memorable sequence in the book.

Then, of course, there are the cases that aren’t solved. There are the times when Rinek was too late, the bodies that haunt him, the near misses, the knowledge that eventually consumes him with anxiety and depression.

While In the Name of the Children is authentic and filled with horrifying and memorable stories, it somehow didn’t fully resonate with me. I’m not entirely sure why, but part of my suspicion is the fractured nature of the narrative. We spend a good portion of time with Rinek in the beginning, watching him get into the FBI, overcome the physical strain of the requirements and the prejudiced culture, watching him work his way up and face unfair and unjust circumstances. But once he makes it, the story transfers from the memoir-like closeness to one of vignettes. Some of the vignettes are obvious choices. Rinke’s work on some famous cases, for example, must be included.

Yet, other vignettes don’t entirely fit or, at least, Rinke never tells us why they are so important to him, so memorable. They’re merely small (horrifying) asides, but by now Rinke has sunk back, away from us, relating fact only. In the end he does come forward, briefly, again to show a very small personal look at the devastation of the job on him, but it’s only a snapshot. One that is carefully layered and curated. We never really got close to Rinek again. This creates a distance. Perhaps it was one the author psychologically needed to write about these cases, yet it harms the intensity of the emotion and our connection to Rinek as a person.

In the end, the book was just ok. I wanted more of Rinek and less of a blow-by-blow detail on the cases. I could get this from a newspaper or a court report. Instead, I wanted to hear about the human side – the victim’s, the killer’s, and most importantly Rinek’s.

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019