Cotton, Crimes and Capitalism…

Author: Edward E. Baptist

From the very beginning, historian Edward E. Baptist makes an interesting choice in his history of slavery in the United States. He repeatedly refers to the “enslaved people” who form the core of his narrative, never once calling them slaves. And lest you think this is a trivial distinction, I think his choice clearly makes the point that words truly matter. It’s much easier to treat people as subhuman beasts if you call them something else, denying their actual humanity. It also serves as a clue that The Half Has Never Been Told doesn’t present the traditional account of slavery during the United States’ initial four score and seven years.

From the very beginning, historian Edward E. Baptist makes an interesting choice in his history of slavery in the United States. He repeatedly refers to the “enslaved people” who form the core of his narrative, never once calling them slaves. And lest you think this is a trivial distinction, I think his choice clearly makes the point that words truly matter. It’s much easier to treat people as subhuman beasts if you call them something else, denying their actual humanity. It also serves as a clue that The Half Has Never Been Told doesn’t present the traditional account of slavery during the United States’ initial four score and seven years.

As the title alludes, Baptist – an associate professor of history at Cornell University – tells a previously unacknowledged story of slavery, one that is inextricably tied up with the story of American capitalism. Starting at one of the key economic transition points in the history of North American slavery – following the American Revolution – the author describes how slavery switched from primarily sugar cane production in the Caribbean to cotton production in the rich soils of what is now the southeastern US. As the natives were herded westward from their homelands and Louisiana was purchased from the French, more and more land was made available for the ever expanding cotton industry.

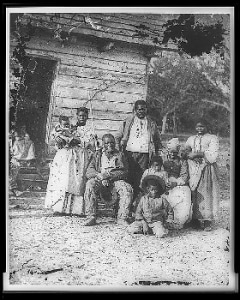

Known as King Cotton. The fluffy white bolls quickly became the most important commodity of the 19th century, feeding the enormous and inexhaustible textile mills of England. But much like oil in the 20th century, the more crucial the commodity the more violent the sins that are allowed in its name. Each boll had to be picked by hand and each and every one of those hands belonged to enslaved African Americans, whose efforts rapidly made the US the newest economic power on the international block. As profits soared, the drive to ramp up production became irresistible to the cotton barons of the day, resulting in increased use of whips, plows and the forced migration of enslaved people from their homes in Virginia, Maryland and North Carolina to the Deep South, where their labor in the vast cotton fields was more valuable.

While Baptist doesn’t hesitate to detail the frequent violence that was committed by southern enslavers to try and increase cotton profits, he is clear in his indictment of the many capitalists in the North and in Europe who knowingly financed the cotton trade, seeking out the highest possible profits from their investments. The intricate financial web created by this burgeoning cotton market made it increasingly difficult for abolitionists to gain much traction in their anti-slavery efforts as the politicians and power brokers of the early 19th century were full vested in this new American economy.

The author also reveals how African Americans weren’t just enslaved – appalling as that is – they were systematically tortured to force them to keep pace with unrestrained market forces. Some enslavers even kept detailed records of their atrocities, delicately calibrating the torture for those who didn’t meet their cotton picking quotas.

But Baptist’s book is much more than a history of slavery. It’s also a cautionary tale of the dangers of unregulated capitalism, a philosophy that can be used to maintain that since whipping enslaved people increases profits it must be right. The author successfully argues that this unflinching view of capitalism can provide lessons that apply to present day free market enthusiasm. Much of the opposition to emancipation was fueled by enslavers who argued that the government didn’t have a right to restrict the use and control of their property, arguments that resonate today when government attempts to infringe on the immoral actions of big business. Moreover, many of the shady financial deals that led to the economic collapse of 2008 were first invented during cotton’s heyday in the early 19th century, as enslavers and investors tried to leverage their holdings, creating private profits when they succeeded and public losses when the failed.

Writing with great power and poignancy, the author’s work is much more than just dry history writing. Maybe as a result of his passionate prose, he has been accused of excessive “advocacy”, most pointedly in an anonymous review in The Economist, which accused him being too hard on white enslavers. While the review never actually addresses Baptist’s economic arguments, it pedals the old trope that the atrocities of American slavery were the result of a few white bad apples, rather than being an essential part of slavery’s inherently rotten core.

Horrific organized violence. Brutal forced migrations. Heartbreaking family disruptions. Systematic rape. Such are the outrages that lie at the very roots of American capitalism’s birth story, as revealed so effectively in The Half Has Never Been Told. Baptist contends that it was these crimes against humanity that built the United States into an economic giant, much more than the traditionally cited hard-nosed Puritan work ethic or Yankee ingenuity. It’s an argument that’s sure to stimulate thought for any open minded American history enthusiasts. Highly recommended.

— D. Driftless

Dave’s review of another eye-opening book about slavery: The Counter-Revolution of 1776.

- Best Non-Fiction of 2016 - February 1, 2017

- Little Free Library Series — Savannah - May 22, 2015

- Little Free Library Series — Wyoming - November 30, 2014