Redcoat Django…

Author: Gerald Horne

Everybody knows that the American Civil War was about slavery. But contrary to what you may have learned in high school, African slavery was equally important as a trigger of the American Revolution, four score and seven years earlier. At least that’s the surprising argument that historian Gerald Horne makes in The Counter-Revolution of 1776. Supporting his thesis with a copious amount of historical documentation, he presents a thoroughly convincing case and turns the conventional view of the United States’ birth story completely on its head. Unfortunately, while the book is chock full of astonishing historical revelations that I found both illuminating and intriguing, it’s also the most awkwardly written book that I’m ever likely to recommend.

Everybody knows that the American Civil War was about slavery. But contrary to what you may have learned in high school, African slavery was equally important as a trigger of the American Revolution, four score and seven years earlier. At least that’s the surprising argument that historian Gerald Horne makes in The Counter-Revolution of 1776. Supporting his thesis with a copious amount of historical documentation, he presents a thoroughly convincing case and turns the conventional view of the United States’ birth story completely on its head. Unfortunately, while the book is chock full of astonishing historical revelations that I found both illuminating and intriguing, it’s also the most awkwardly written book that I’m ever likely to recommend.

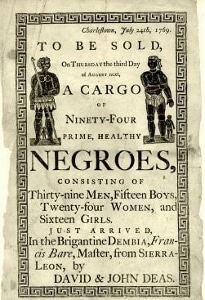

Long before the Battle of Lexington and Concord, having built a vast economic engine and generated massive profits on the backs of African slaves – from New England to Georgia – the European settlers of colonial America were becoming increasingly disturbed as London was gradually leaning toward the abolition of slavery. Unwilling to accept the idea of freedom for Africans or to even consider loosening their cruel bonds a bit, the pro-slavery colonists rallied together to oppose Britain and the hated redcoats.

In great detail, Horne – a professor at the University of Houston – highlights many of the slavery related incidents that eventually culminated in revolution from the British crown. Affronts such as taxes and restrictions on the slave trade, conscription of settlers to oppose the Spanish and the French, and the arming of Africans to defend the crown caused the colonists to eventually lose trust in London’s motivations. In addition, legal decisions and commentary from the eastern side of the Atlantic were increasingly arguing that Africans might actually have some rights as human beings, frequently criticizing the particularly brutal strain of slavery practiced in places like Rhode Island, Virginia and the Carolinas. By providing a slave’s perspective on these pivotal events, Horne lays out an unconventional, but an entirely convincing, interpretation of pre-revolutionary colonial history that I found quite eye-opening.

Ironically – but rather unsympathetically – Horne spends much of the book discussing the terror that the European settlers endured in the decades before the Revolutionary War. When they weren’t being attacked by the French or the Spanish, they were being ambushed by warriors from the indigenous tribes. But an even greater fear was that they would be slaughtered in their beds or poisoned at their tables by their own African slaves. The author chronicles dozens of slave uprisings from Manhattan to South Carolina, Jamaica and Antigua, each one more horrifying than the next. But in spite of these very real fears, the merchants and settlers continued to bring more slaves into the colonies – a routine that was sure to increase profits, but was also likely to increase the chances of a bloody slave revolt. According to Horne, the deliberative bodies of the day spent much of their time struggling to determine the ideal ratio of slaves to whites. But despite having a full understanding of the dangers; like drug addicts the settlers always wanted just one more ship full of slaves.

Revealing the author’s Marxist philosophical underpinnings, the book also sheds light on the birth of modern capitalism in the early 18th century, as increasingly powerful private business entities assumed the reins of the economy from the monarchies of Europe. Horne doesn’t hesitate to point out that most of the fruits of this economic bonanza that many of us enjoy to this day had their origins in the vicious slave trade of colonial times. Modern economic marvels like the skyscrapers of New York City and the vacation mansions of Newport, Rhode Island ultimately owe their existence to the incredible fortunes generated by trading in the flesh of Africans.

Unfortunately, Horne’s writing style makes the reader struggle through thickets of verbiage in order to reveal each nugget of historical illumination. Plagued by convoluted sentences, poor organization and a frequently wandering focus, the dense prose is quite formidable and suffocating. While the various pieces of the story start to come together near the end, I used up every ounce of my considerable stores of literary fortitude just to get there. It’s rather upsetting, as there are dozens of great stories in this book, but they don’t get off the ground due to the lack of skilled storytelling.

Prior to reading this book my simple-minded understanding of colonial times in America can best be summed up in two words. What slaves? African slavery is so completely removed from the traditional story of the American Revolution as to be entirely invisible. Loaded with plenty of extraordinary evidence to support his extraordinary claims, Professor Horne attempts to correct this deficit in The Counter-Revolution of 1776. The book sheds entirely new light on the idea of freedom, which was won at the expense of the thousands of Africans who yearned for liberty as much as any of the founding fathers did. While I struggled through it, I have to say that it’s been a long time since a book caused me to think so much. Despite a plethora of sentences from hell, I can still recommend it for anyone interested in American history. It’s worth the effort.

— D. Driftless

- Best Non-Fiction of 2016 - February 1, 2017

- Little Free Library Series — Savannah - May 22, 2015

- Little Free Library Series — Wyoming - November 30, 2014

Leave A Comment