H is for Healing and Hardship

H is for Healing and Hardship

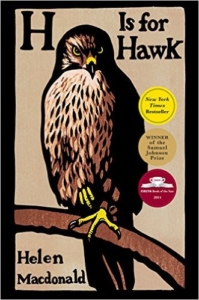

Author: Helen Mcdonald

With unanimous agreement, my book club long ago selected our July pick – Helen McDonald’s non-fiction mélange of hawk raising and recovering from the grief of losing her father, H is for Hawk. With a string of accolades and awards ranging from Oprah to the Washington Post, all the buzz this year has centered on this eccentric story of a lonely woman, the vastness of loss, and the violence of nature. Starting the narrative with a wide spectrum of nature’s beauty and the odd foreboding of impending loss, which soon comes in the usual innocuous way: an unexpected telephone call, Mcdonald interweaves mastery of language with vivid, Technicolor description. The symbolism in places is raw, the correlations obvious, and in other places barely discernable beneath a churning surface of letting go.

Helen’s father, a former journalist and plane aficionado, grew up in a time of war when death dropped from the bellies of planes sailing through clear skies. His fascination with planes was part fear and part mastery of that terror, and his way of handling the world rubbed off on his impressionable daughter. Going through the sudden (and greatly unexpected loss) of her father, without even a chance to say goodbye, Helen returns to her equal fascination with flight. But, instead of shining metal bellies she prefers the intricate striations of feathers and the ruthless gleam of intelligence emanating from a living animal. Fascinated by hawks and falcons even as a very young child, Helen now decides to do something she never expected to do: raise and train a goshawk. She’s experienced with falconry on every level although goshawks have never been her particular interest. Yet now, suddenly, in the wake of her father’s permanent absence, the training of a new type of bird becomes the essential distraction and the best excuse to avoid people and remain locked away both from the outside world and her own internal reactions to the grieving process.

Combining denial with a certain wild grief, Macdonald merges dangerous depression with extreme stoicism. Mable, the adorable bird compatriot of Helen’s days, is an open book to us. We are used to her fierceness and also her strange playfulness. Her needs are alien and her own, yet Helen starts to see herself as a hawk, wanting to be at one with Mable in this world, no doubt because civilization and people hurt her too much. Seeking an escape through her hawk, Helen nearly goes wild herself, participating in the bloody kills, introspecting on the mechanism of death she has released into the world and trying to puzzle out the brutality of killing and its place in the dance of life.

As the story goes forward, Macdonald discusses T.H. White’s book The Goshawk. White is the children’s author of the modern day Merlin stories (think of the movie The Sword and the Stone which was based upon his re-imagined Arthurian legends.) White was secretly a sadist and a homosexual in a time and place where neither were socially acceptable. Forced to bury his true identity, and also to feel extreme guilt for his predilections, White dated many women and often tried to fit into the normal pattern of society, only to fail and, in so doing, cruelly hurt others. White seeks solace in raising a goshawk as well, but all of his falconry is bad. Despite his brutal childhood and terror that he will give in and hurt others, White cannot seem to keep cruelty under wraps and he oscillates between mistakes and conciliation to his perplexed and bedraggled goshawk. An account that has long deterred Helen, in the shadow of her own grief, and therefore loss of identity in the world, she suddenly sees White’s tragic life and struggles as a touchstone even though, from the reader’s perspective at least, the two seem extremely different, each with separate problems.

As the story goes on, Helen hides behind her beautiful prose and flourishing descriptions as White’s story takes over. Helen’s loss is still there, palpable behind the deliberately protective barriers of carefully chosen sentences, yet it’s White that the story is really about. White with his struggles, his hopes to fit in, his desire for redemption, his fear of the wounds that he bears thanks to a truly horrific childhood. And when White isn’t in the forefront our protagonist is the elegant Mable, strong of wing and delightfully interesting, especially for those of us with limited knowledge about the life of a hawk.

What’s most interesting, and the most disappointing, is that with all of these deep emotions, intersecting introspections, speculations, transcendence, and understanding of life and death painted through nature and the story of a long dead author, Helen herself is barely there. It’s evident that she doesn’t fully understand her own grief and while her actions and reactions are testament to the fact that her life is teetering on the edge, her emotions inexplicable and explosive, her stoicism and evident inward struggle remain hidden behind careful drawn panels with the occasional hint of something more. Helen talks about falling in love with a man after her father’s death because she needed to place her hopes and her love on someone. He wasn’t the right man, apparently, and this sudden relationship is indicative of Helen’s inability to see her way through the trees . . . yet, we’re only given tidbits. The emotional revelations, the moments of missing, the pain of being inside her head instead of watching the outward manifestations of inner turmoil, are all carefully concealed and in the end, we know White and we know Mabel, but Helen remains aloof. She eventually comes through grief into the other side, but despite the atmospheric prose, readers ultimately don’t feel like we’ve been part of her real, hidden journey. While the strange ways grief manifests itself are displayed (i.e. sudden hawk raising and fascination with the life of White), it’s not enough to capture the true inner turmoil of Helen or to give us a glimpse into who she is as a person. She remains emotionally dead, which was indeed her experience of grief and which is a natural reaction, yet for writing, this leaves readers clutching a sad book feeling like we were never really let into that world – and maybe we should be grateful that we were not.

– Frances Carden

- Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

- Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews/

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019