Growing Up Black In America: A Man’s Letter to His Son

Growing Up Black In America: A Man’s Letter to His Son

Author: Ta-Nehisi Coates

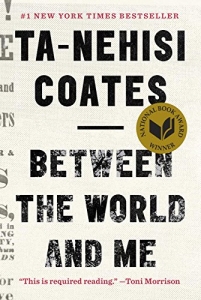

For our impending May discussion, my book club selected Ta-Nehisi Coates’ award winning non-fiction narrative, Between the World and Me, which is a heartfelt stream-of-conscious letter from a black man to his son warning of prejudice and the continual fight for the safety of the black body in America. For Coates, an esteemed writer for The Atlantic this is his second published book and it won the 2015 National Book Award for Nonfiction and was a finalist for the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction. Even more imminently (to my book club at least) the author is local to the Maryland area (hailing from Baltimore).

The book is short, brutal, filled with palpable emotion and a weighty sense of doom and addresses such incidents as the Trayvon Martin case and more personal stories related to the author’s own experiences of prejudice and police brutality. Coates only sought the acclaim of one author, Toni Morrison, who read and highly recommended this book, citing it as required reading. Yet, somewhere in between all of the rage and the issues, the full circle knowledge and understanding of a corrupted and perverse world is never brought to full fruition. We enter the struggle with the author and in the conclusion, he leaves us there hopeless, demoralized, and ultimately angry. It’s not exactly a satisfying read, but then again, it never intended to do anything beyond warn. Indeed, despite the desire for justice and the full rage which highlights each page, it’s not even truly a call to action but something between a requiem and a dream of unfulfilled vengeance.

Imbued with the unequivocal love and fear of a parent, the story is told to “you” (in this case, his teenage son who is just now encountering the injustice of the world and the realities of racism.) In using such a voice, readers are instantly in Coates’ camp and even for those non-parents in the crowd, the paranoia and fear for a child for whom, ultimately, you cannot protect from the greater realities of life, is a captivating and heart-wrenching prospective, even more so because it is a non-fiction letter and therefore, all representative of true feelings. Inspired by the latest episode of police brutality, Coates writes to his son as he emerges from his childhood bubble of safety into the grand unfairness of the world. Coates himself is no stranger to this awareness and unlike the son he has tried to protect, knew from the beginning the cruelty of living. Growing up in a Baltimore ghetto, Coates tells stories of street gangs, children pulling out guns on him, the stark difference between what he had and what the American dream promised (and showed vividly on television.) Coates himself ascribes what he relates as black-on-black violence (my terms) as a necessary outlet for generations of oppression by those who “think themselves white.” This gets into the complicated heart of the narrative where Coates oscillates between vivid memory, theory, and conjecture.

The narrative has a point, but in the fashion of letters, it is meandering and through this searching style we sense the author’s own desire for an explanation, for a universal truth which ultimately he does not find. White America oppressed his ancestors, using the blood from their sweating backs to build a rich empire and as such has been breed to continually oppress generations of African-Americans. Nowhere does Coates feel that this is more evidenced than through the authority of the police who, he proposes, are always ready to destroy a black body. Indeed, the very concept of the physical body is the key, reoccurring theme here, as Coates continually states that a black body does not truly belong to its owner and is a fragile thing in that the white-supremacist system always threatens the safety of the body either directly (police brutality) or indirectly (through causing generations of fear that lead to black-on-black violence, the natural outlet inherent in living in continual terror of bodily harm.)

As we grow up with Coates, we adventure into his college experience at Howard University, which he refers to as the Mecca. It is here that his theories and views of life meet their first challenges since he cannot accurately define oppression despite the wealth of research at his fingertips. Here, he cultivates a strong love of Malcom X and yet, he cannot fully find the answers he seeks. He acknowledges that Africans sold their own people as slaves, and that other races and cultures over time have had similarly awful experience and societal prejudice levied at them. There is no direct answer for the why, and Coates seems to struggle, allowing the narrative to muddle as his own mind is overcome by the information overload and the basic, boiled down question: why is the history of humanity so cruel. Here is where the narrative starts to fail because Coates flails briefly through confusion but never answers or returns to his own question, instead pursing the notion that only black oppression matters, glossing over so many wrongs done across the world and the horrors of history itself. As readers, these big questions he has raised demand answers at least in the fact that we want to see the author deal with them or admit that he cannot accurately answer them.

Further, Coates offers a bleak view for his son. A staunch atheist, Coates notes that the only beauty and only lasting truth is in the body itself, which as has been noted, can so easily be destroyed. This offers his teenaged son what seems like a testament of defeat before the battle of life has even begun. There is no hope in the hereafter, no comfort in the knowledge that at the other end of suffering is reward, and instead Coates notes that in his view, America has not progressed beyond its slave owning years and the world is just as bad as always and will remain so. It’s enough to make readers slouch back, disheartened, with a “why even bother living” sentiment strongly etched in words that Coates seems to think are encouraging. You only live once, defend your fragile body, son, is what he seems to say. There is no escape even when away from the ghetto because the forces that created the oppression are active in a hundred different ways and places. Life, in other words, is a no-hoper all the way through if you are born black (according to Coates).

The narrative includes some truly devastating sequences specifically the personal instance of unwarranted police brutality when Coates’ young friend (Prince), an up-and-coming, much beloved and hardworking man, is shot in the streets by a policeman who is never punished for the wanton taking of a life. Later, with a child in tow, Coates sees his young son shoved by a white woman and when speaking out is accosted by an entire crowd of white people – an instance that when related both makes the blood boil and simultaneously chills the heart. These personal experiences are powerful, as is the evidence of history and current events – yet as a white person, it’s difficult to read the narrative without screaming. Not all white people are racists and not all who consider themselves white are inhuman monsters. Of course, some are and these, naturally, are the ones who speak the loudest and cause the most grief in the world. Yet Coates is attached to a reverse stereotype, seeing all white people as former slave owners adamant to grab a black body again and crush it. This is disturbing and is itself racism showing how the harm that people do, one to another, creates an unending circle. To me, at least, the problem is not merely one of race. It’s not that simple. The problem is that, throughout history and across the world people are always finding arbitrary means to designate themselves better than others, to kill and crush to make themselves safe and great. It’s horrible. It’s evil. And it’s more widespread than the issue of white and black. This is a human problem, across all borders, and while Coates makes some vibrantly good points, his argument fails to go all the way and acknowledge the greater tragedy that bleeds into life and makes people hate each other. It’s this narrowness of his view, which focuses solely on how the world affects him and his son, that takes what is admittedly a powerful (and beautifully written book) and degrades its message with so much hate and so much liberal, blanket stereotyping of its own.

– Frances Carden

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019