A Slice of Life Collection Set in an Evolving India

A Slice of Life Collection Set in an Evolving India

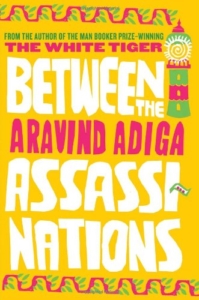

Author: Aravind Adiga

Long fascinated with the rich history and social complexity of India and its evolution away from tradition, seeing Between the Assassinations in my random eBay audiobook lot ignited a spark of enthusiasm. On another long trek across states, the fiancé and I tucked in with bad road food, plenty of snacks, and this promising book touted as the showcase of an aspiring new author. Pastel writing on the shiny plastic sleeve bragging about “Man Booker Prizes” and the rise of a brilliant new literary voice further raised the expectations – while also making me secretly a little nervous that this hodgepodge collection of short stories was going to be more cerebral and vague than visceral.

My background with India is relevant only in that most of my coworkers are from India, including different regions both rural and urban. One coworker in particular is from a rural village in India and is open to talking about the changing dynamics of culture and daily life. Strongly felt prejudices between groups are still very much felt, even to the unwary American eye. For instance, resentment exists between Indian residents in the city and those in the country, northern and southern Indians, Indians of lower classes verses their priestly Brahmin high class, and of course, juxtaposing religions (mostly Hindu and Muslim.) All of these social indicators make a marked difference in the daily life of an Indian and while it’s not all pretty, it’s still very real and slow to change.

Listening to work friends and colleagues has created a disparate picture of India for me. On the one hand, I hear of the beauty, the loyalty of family, the comfort of tradition, and even some comical elements (the problem of monkeys who like to terrorize small villages). But then, this is all brutally juxtaposed by the lamentations about the poor to non-existent medical care. Perhaps the most striking moment is the sheer wonder I see in my coworkers as they watch their children come of age and thwart expected elements such as arranged marriage. Even more pronounced are the fears and very real cultural rebellion of sending female children out into the business world, taking a man’s place both intellectually and, even more shockingly, in the role of supporting family. This further disparity between men and women is occasionally remarked on by a particularly close friend who as the father of daughters is torn between the system he was raised in and the patriarchy which leans heavily against his own children. Watching women finally take on roles beyond homemaking and participating in education is violently contrasted with the proclivity to treat women as property and the status affiliated to a woman by her marriage and not her intellect or ability. It was all this, a culture tilting, sometimes spinning out of control, often cruel and beautiful in the same breath that drew me toward the promises in these short stories. I only see the tip of the ice burg, the occasional dialogues that are shared with me, and behind it all I still wonder what these furtive conversations fail to express and capture. There is so much more to India in so many ways, and it often goes unnoticed or merely categorized as “third world.”

So with these expectations, or should I say raw questions, it was easy to be disappointed. Between the Assassinations is ostensibly a collection of unconnected stories set between the assassinations of Indira Gandhi in 1984 and her son Rajiv in 1991, neither of whom are mentioned or relevant within the stories. It all takes place within a few weeks in a fictitious Indian town and is interspersed with tourist like guidebook quotes.

While Between the Assassinations does detail the starkness of life for the lower castes as averse to the life of the wealthy Brahmins, the composite is altogether too focused on an incompletely articulated bitterness. The characters are confused, one might even say shell shocked, and while this is so evident of those who live on the brink of starvation and destruction, the aimless slogging through the days doesn’t translate well onto a page or create a story. It’s not that we need to be entertained. We need to be awakened here. The problem is the characters are in a stupor with their own despair and while this speaks and makes a point, it misses the defining connection that takes the reader beyond a mere book and into social, international, and personal considerations. India here is a big Sylvia Plath poem, all despair and aggravation, and bleak, loud ugliness, but there is no ultimate point or even a cohesive complaint. It may very well echo the despair of life on the edge, but do readers really get the point or hear a call to action? Are we really even educated or is this just another of those disaster story collections of those vague “less fortunates.”

All this isn’t to say that the collection is unworthy, just incomplete feeling. Perhaps it just tackled something too big or perhaps I was wanting answers to questions which, in and of themselves, cannot be defined and neatly slotted into a story with beginning, middle, and end. All of that aside, there’s a lot here. Some stories are more effecting than others and the topics covered typically deal with religion, caste, and the issue of wealth and the lack of a “middle class.” In one especially memorable and lengthy story a man who runs with a cart to perform deliveries everyday oscillates between just surviving and an all consuming rage which is so palpable and elemental that despite the despair in his plodding day, readers are unable to fall into a depressing, lifeless malaise. We want to run by that man and we want to explode with him as he battles not to become a merely reactionary (and obscenely angry) animal.

In another story, a disenchanted student sets off a bomb in his class, a statement against the caste system. It’s a topic and a situation that should be serious but instead devolves into a mockery as the teacher, fumbling with a speech impediment, yells at his class “You puckers! You motherpuckers!” In the end, confession itself is a joke as the system accepts neither honesty nor legitimate repentance. There is no room for change, no place for honesty, no marketplace for confusion or regret. All this is denied existence, just as a serious situation becomes a tragic comedy.

Perhaps most memorable, in one of the collection’s later tales of a young girl begs for her shiftless father to support his drug habit. Her entrapment in an abusive parental relationship is merely a mirror of the society that surrounds her and showcases the irony of boxed living where everyone exists in their own private hell and together builds bigger and bigger replicas of their particular purgatories.

In other stories we meet similarly unique characters: a married couple who despite their happiness are seen as eccentric since they have opted to have no children; a man who works his way from spraying a rich ladies garden into becoming her invaluable servant and through one moment of forgetfulness losses everything; a man sent away from his family and new in town aspires to be the best bus conductor but each night must bribe a gangster for a slot of ground in a back alley to sleep in; a Muslim boy seeks employment but is looked down on by his Hindu compatriots only to conversely judge them just as harshly, and so on. It’s “slice of life” type of writing with the brutal smack of realism and the grittiness of street life.

Written half like a guidebook and half like a series of disconnected events strung on an idly flicking necklace, the stories have no cohesive whole and no real direction. They simply are, and in this they flaunt their beauty and also their weaknesses. The issues Adiga concentrates on are the ones we traditionally expect to hear, yet the spectrum isn’t quite wide enough and the emerging role of women is distinctly absent. Indeed, the few female characters are disappointingly one dimensional, dare I even say bitchy, and while the pathos for the male characters shines with emerging individuality and a roughly defined sense of self-worth, other cultural issues are skimmed over or simply not addressed. It’s incomplete and since none of the stories themselves have a central theme (or an ending) the last page feels like a letdown. We’ve read so much – been through so much – but where do we take it and what do we do with all these incidents, some stunning and some mundane? I mean, when the chips are down, what does it all mean, if anything. Is this merely a shadow play of episodes in the life of various people and, if so, why are we always cut off when the story seems to find direction, when an ending or some sort of culmination is promised? If Between the Assassinations is an opus of “a moment in the life of” dedicated to the emerging citizens of an evolving India, so be it, yet a feeling of closure or of continued action after the last page is needed. Instead, a certain stasis pervades and the final feeling is one of listless acceptance. It’s like there are still a crucial ten pages missing that will tie it all together and say why these people, why at this time, why at these moments, and why we, in particular, are being told. Regardless, incomplete or otherwise, the collection opens up a small spotlight on a big country and in the attempt alone, I applaud it.

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews/

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019