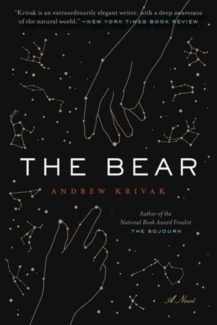

Magical Realism and the Last People on Earth

Author: Andrew Krivak

Magical realism intertwines with survival in this purposefully sparse, literary apocalypse tale. Only two humans (seemingly) remain, the end of their civilization relegated to a past far away enough that memories of what happened and the staples of civilization – including the strangeness and artistry of glass and close croppings of buildings symbolizing dense communities – are more enigmatic than talking animals and the nature of death. The two humans are a father and daughter who live in a handmade cabin and live off the breathtaking harshness of a forested world. It starts as the daughter grows up, climbing the mountain that looks like a bear to witness the cairn that is all that remains of her mother. This yearly ritual is her only connection to a past she does not remember, and when an ill-fated journey to the sea (for more salt to cure meat) leaves her orphaned, the tale turns from mere survival into something deeper that attests to the enduring nature of love and the seasonality of all things.

In the beginning, the deliberate mystery is tantalizing, and we cannot really get a bead on how long ago this worldwide apocalypse occurred. What’s unexpected, at least in the ordinary progression of all stories with end-of-the-world tidings, is that the usual smoking crater and grapeshot of war is nonexistent. Nature, beautiful and feral and somehow so right, is all that remains, the world not a scar but a glowing green spot that seems not to miss humanity at all. We briefly see a set of eroded beach condos or townhouses, and yet these have mostly been subsumed back into their natural landscape, a previous ending that seems like it must be very far in the past (fifty to a hundred years at least). We wait for answers – is this some result of disease, man-made or otherwise, and are there other troops of lone survivors making their own way and destined to run into our devastated orphan (for better or worse). Ultimately though, answers are not the intention and the hints, at first a compelling little mystery that we expect to unwind over a camp fire, are instead extinguished. It’s ultimately unbelievable that the Girl never asked her Father as she grows older what happened and why (and how) they were spared, and so we assume she did. This is a scene then that the author has shielded us from, and the choice is a strange one that doesn’t altogether resonate. It is evidentially the end of humankind’s dominion, and in the nature of a fable we are expected to accept and take the moral of transition and endings as some sort of inevitable, bittersweet yet beautiful thing.

Instead of answers then we have a Robinson Crusoe like subsistence, although with this scene set against the escalating harshness of a mountain winter as opposed to susurrating sand blowing across a blank horizon. Krivak spends his time with images of saplings bending under skilled hands, transforming into snowshoes, and deer-bone tipped arrows spearing fish in rushing rivers. Sometimes the imagery is intensely detailed, which if not the most interesting focus is nonetheless well rendered and essential to the elemental concentration on survival. The hunting scenes aren’t for all of us, especially as an early on scene has the Girl killing two parent geese who scared her (her intention not spur of the moment but planned out of a childish vengeance), leaving the little goslings for “the foxes to take care of.” This then is an earthy, hardened character, and those of us with love for animals and the nurtured softness of a life where the dirty work gets done, processed, and delivered in non-bloody packages to grocery stores may find themselves a bit squeamish. The gosling scene and how unnecessary their murder was for both survival and food remains to haunt. Indeed, if it hadn’t been for this scene the other moments of respectful and necessary hunting would not have bothered me, and would have allowed me to see the character in a more favorable light, not of unnecessary harshness but of desperation and a calm acceptance of the circle of life and death.

Instead of answers then we have a Robinson Crusoe like subsistence, although with this scene set against the escalating harshness of a mountain winter as opposed to susurrating sand blowing across a blank horizon. Krivak spends his time with images of saplings bending under skilled hands, transforming into snowshoes, and deer-bone tipped arrows spearing fish in rushing rivers. Sometimes the imagery is intensely detailed, which if not the most interesting focus is nonetheless well rendered and essential to the elemental concentration on survival. The hunting scenes aren’t for all of us, especially as an early on scene has the Girl killing two parent geese who scared her (her intention not spur of the moment but planned out of a childish vengeance), leaving the little goslings for “the foxes to take care of.” This then is an earthy, hardened character, and those of us with love for animals and the nurtured softness of a life where the dirty work gets done, processed, and delivered in non-bloody packages to grocery stores may find themselves a bit squeamish. The gosling scene and how unnecessary their murder was for both survival and food remains to haunt. Indeed, if it hadn’t been for this scene the other moments of respectful and necessary hunting would not have bothered me, and would have allowed me to see the character in a more favorable light, not of unnecessary harshness but of desperation and a calm acceptance of the circle of life and death.

Where the story gets interesting, and wonders away from the Crusoe-like machinations of base survival, is when the forest itself comes together to help what is soon, obviously, the last remaining human. The impetus of the animals to do so, and the supernatural semi-assumption that the dead Father is somehow involved, never truly takes shape. In the form of all magical realism, we end up accepting and marveling instead at how the unexpected becomes the usual. As the title more than implies, the Girl’s main companion becomes a bear, who shares the secrets of the forest language with her and leads her back on her final journey from the horrors of the sea and the isolation of mountain winter to her now empty home.

The Bear has that intense literary feel of deep meaning, although the actual answers it purports are not there – or at least not brought to life. In the end, then, it transforms instead into a bizarre and interesting travel story, one about survival that is less real and more fever-dream. At times, we wonder if the grief of loss has driven the character to madness, towards visualizing a kinder world where her Father lives on through the help of the forest and the animals themselves prove that she will not now live and die in silence. I’m not sure, especially based on the conclusion, that this was ever the story’s intention, yet the possibility is there and the meanings of that interpretation perhaps deeper than the standard focus on a forgiving and interconnected nature where things end.

The Bear has that intense literary feel of deep meaning, although the actual answers it purports are not there – or at least not brought to life. In the end, then, it transforms instead into a bizarre and interesting travel story, one about survival that is less real and more fever-dream. At times, we wonder if the grief of loss has driven the character to madness, towards visualizing a kinder world where her Father lives on through the help of the forest and the animals themselves prove that she will not now live and die in silence. I’m not sure, especially based on the conclusion, that this was ever the story’s intention, yet the possibility is there and the meanings of that interpretation perhaps deeper than the standard focus on a forgiving and interconnected nature where things end.

In the conclusion The Bear is an interesting book, vividly written and skillfully brought to life, yet ultimately incomplete, more idea than manifestation. Readers will enjoy the story, but as the Father and the Girl are destined to be forgotten by their own ending world, they are ultimately forgotten by us as well. They are somehow untouchable and alien, even in the shroud of their promisingly poignant this-is-how-it-all-ends nature eulogy. We sigh, we read and wonder, we examine the bear and the meaning of its friendship, and the necessity of help, and yet ultimately move aside having only gotten glimmers of the meaning, like the edge of a charred bone burred beneath pristine, unmoving snow.

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews/

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”1942658702″]

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019