Why Hemmingway’s Great Classic Feels So Empty

Why Hemmingway’s Great Classic Feels So Empty

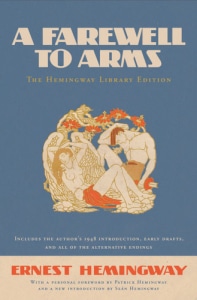

Author: Ernest Hemmingway

Unfolding against the bleak landscape of the Italian front in World War I, Hemmingway’s semi-biographical novel follows American Lieutenant (“Tenente”) Frederic Henry who serves as an ambulance driver in the Italian army. Carousing from one whore-house to the next, the Tenente regrets the very blandness of his own existence and seems so far jaded by it that he legitimately has no interest in whether he survives the war. Whether a product of his times, a dissolute soul overcome by the war, or a victim of personal tragedy, we meet the Tenente when he has already lost all hope of life, his very bleakness sans explanation the motif for an exceptionally postmodern representation of a disenchanting world.

Between idle chats with his fellow ambulance drivers, episodes of priest bating, and spiritless parties, the Tenente starts dallying with the affections of one Catherine Barkley, an English nurse who lost her fiancé in the war. Beginning as mere entertainment, his proclamation of love a mind-game somewhat more intriguing than the easily acquired prostitutes, Catherine’s unique outlook and easy going nature begin to captivate the lieutenant in more ways than one. When he is wounded and ends up in a hospital with Catherine, the real love affair begins and our protagonist finds himself captivated by a woman as free from moral rule and social pressure as he is himself. However, sexual and emotional freedom has its irrevocable dangers in a world where medicine and treatment are rudimentary, rare, and ineffectual especially as the hostility of war leads our protagonist to defect. Examining such topics as war, social expectations, love, and the truth behind freedom, A Farewell to Arms is touted as Hemmingway’s greatest book.

Following my classical book challenge, I’ve set up a flawless system that keeps my reading list randomized and refuses to allow me escape from certain books and authors which I don’t relish. This system involves the Easton Press list of 100 greatest books and my determination to go from the top of the list to the bottom, reading everything. For A Farewell to Arms I went with the audio book rendition, bravely read by Alexander Adams.

Purportedly, Hemmingway says so much with so little; it’s his claim to fame and the constant praise I heard in college as we re-hashed and regurgitated Hills Like White Elephants at least once a semester. That being said, other than his famous short story focused on abortion, my exposure to Hemmingway was both blessedly and ignorantly limited. I knew the rhetoric, however. His terseness is used to create atmosphere and effect, promoting the audience to read between the lines and explore the meanings behind gestures and dialogue without using internal narrative and over-explanation. In its own way, I suppose it is brilliant. In A Farewell to Arms the short sentences, the dialogue, the continual repetition of the same words and phrases (“she was a fine girl,” “it was just grand,” “I ordered a bottle of vermouth”) creates a sterile world in which the desperation of the characters is backlit by the fact that they have long since given up by the time we have met them. If you don’t happen to relish a succinct, staccato style, then Hemingway will probably annoy you and this novel in particular will enrage you.

The characters and the world feel dead. Perhaps this is a sign of success. The don’t-care attitude of the protagonists is heightened to the extent that we in turn do not care about them or their world. They are both selfish, strange beings who claim a passionate love for one another but seem more like separate, usurious entities. Frederic falls in love with Catherine partly because of an unwanted pregnancy and her continual emphatic statements that she would take care of it herself, a resourcefulness that leaves him unworried and stunned at her wonderfulness as a woman (i.e. she’s “grand” and “fine” and “just fine.”) Her refusal to marry him and desire to “live in sin” further sweeten the pot, leaving readers to wonder if emotional attachment is the key here so much as a shared ideology and a desire for independence in a haywire world. Psychologically it is interesting, even well presented, but the aloofness of the characters for each other (and even for themselves) leaves readers unattached and unconcerned. We are convinced that they need no one, and so when the stakes are high, we remain detached, unmoved, uninterested.

At the time of its release (1929) A Farewell to Arms received some serious static for being an anti-war novel; and so it is, in a way. And yet, really, the story has nothing to do with war, but more with mindset. The characters perceive themselves as alienated and even while they pretend to dislike this bitter pill, they secretly glory in being all alone and, as it were, above the rules about society. The defection from the army is less about war and more a social statement and the embodiment of a mindset. The war is a catalyst, but anything else in society could be used equally as well to stand in for the desolation of hope and the sheer enervation of a situation that seems endless and unchanging.

The conclusion of the novel, and here I intend to drop some spoilers, deals with the “ramifications” of two people loving each other – the worst horror of all, which is Catherine’s pregnancy and subsequent death. We also get a surprisingly gory scene of the dead infant, wrinkled like a rabbit and slapped by ineffectual doctors attempting to return it to life. The Tenente, for lack of anything better to do, is merely a reactionary observer to the loss of his woman and (not important to him), his child. It’s very ugly, very base and brutal. I suppose his emotions could be understandable, but the callousness just highlights aspects we have already come to find off-putting, somehow cold and completely inhuman. Frederic talks of throwing a log filled with ants onto a fire once, watching them as they scampered senselessly into the flames, thinking how God was like that – how he could rescue but always chose not to. This comparison is supposed to be strong, the punch line of the novel, but the main character’s hypocrisy shines through as he admits he chose not to save the ants, but to drink while watching them burn. If he feels God is like this, it is because he is first like this himself and the actions and reactions of the world around him, even traumatic events, don’t have any true feeling to them. No warmth of rage, no emptiness of grief, no coldness of loss, but all a certain equilibrium of stable dispassion that leaves readers slogging through pages, trying to get to an epically bitter end just to claim we read (and somehow “got”) a supposed classic.

*A Note on Edition: As mentioned earlier, I listened to the audiobook edition read by Alexander Adams. The narrative was as well produce as could be expected. Adams read well, but was unable to bring expression or emotion into a story that was flat and manic depressive. The shortness of the sentences and phrases made reading a challenging chore for both the narrator and for the listeners.

– Frances Carden

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019