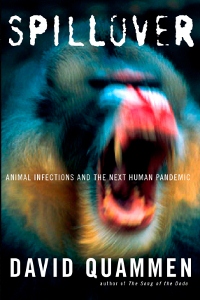

The Next Human Pandemic?

Author: David Quammen

Plenty of people have considered humankind’s demise. A rare month goes by when there isn’t some new post-apocalyptic movie or TV show available for the insatiable disaster-addicted audience. But how might it really play out? Will humanity go down with a bang or a whimper? Well, David Quammen isn’t making any predictions, but in the year 2000, while sitting around a campfire in Central Africa, he got to talking to some men who had witnessed a local Ebola outbreak and it got him thinking. Combining a decade of thinking, researching, traveling and interviewing, Quammen’s efforts resulted in Spillover, a sometimes chilling 500+ page examination of some of the most terrifying epidemics in human history.

Plenty of people have considered humankind’s demise. A rare month goes by when there isn’t some new post-apocalyptic movie or TV show available for the insatiable disaster-addicted audience. But how might it really play out? Will humanity go down with a bang or a whimper? Well, David Quammen isn’t making any predictions, but in the year 2000, while sitting around a campfire in Central Africa, he got to talking to some men who had witnessed a local Ebola outbreak and it got him thinking. Combining a decade of thinking, researching, traveling and interviewing, Quammen’s efforts resulted in Spillover, a sometimes chilling 500+ page examination of some of the most terrifying epidemics in human history.

An award winning science journalist, author of The Song of the Dodo and frequent contributor to National Geographic, Quammen’s goal is to figure out when (or if?) the next big human pandemic will occur and what we can do to control, stop or prevent it. He and the scores of experts he consulted may not be able to predict when this might happen, but they’ve some reasonable ideas about what it might be and where it might come from.

The truism that this book revolves around is that “everything comes from somewhere”. Many of the nasty infectious diseases that affect humans come from other animals who act as a reservoir or amplifier of various viruses or bacteria. Think rabies. Even diseases that appear to have no non-human hosts like small pox or measles were undoubtedly passed on to humans from some other species back in the remote depths of time. Quammen delineates what he fears may be an approaching perfect storm: continued invasion of humans into the last remaining wild areas; unrelenting crowding of domesticated animals; human overpopulation; and instantaneous worldwide travel. Combine these four factors and the risk of some previously unknown virus going pandemic starts to become worrisome.

In eight massive chapters, Quammen reports how close calls happen all the time. He examines the stories of pathogens you’ve likely heard of – Ebola, Lyme and SARS – and others you likely haven’t – Hendra, Nipah and Marburg viruses to name just a few. But listing bug names only tells half the story as all sorts of creatures are required to help deliver them to their unfortunate human victims. Horses, bats, mice, parrots, gorillas, bats, deer, ducks, monkeys, bats and rats, the list goes on and on. Did I mention bats? They come up a lot in this book. Fortunately, these various infections have only briefly flared from time to time and the resulting epidemics have fizzled out with only small numbers of fatalities – hundreds and thousands rather than millions – due to a combination of luck and shrewd medical epidemiology.

Quammen saves the most notorious virus for last. The one new virus in recent history that “got lucky” and has killed up to 30 million so far. HIV. He traces its origins and how it managed to do what few others have done, moving from a single chimpanzee one hundred years ago to evolve into one of humanity’s toughest medical challenges. He goes into great detail, taking a brief and intriguing foray into historical fiction and exploring who the players might have been and the roles they might have played in the HIV pandemic.

This book astounds on four different levels. First, the total volume of research is incredible with a bibliography spanning twenty-eight pages. Second, and even more impressive, the number of experts interviewed and consulted is hard to believe. Quammen has well over a hundred names listed in the acknowledgements, organized by continent, no less. Third, he writes so well. Somehow he’s able to organize this extraordinary amount of information into a readable, engaging and entertaining whole. Despite the harsh topic, he even cracks a joke once in a while. Lastly, and what sets him head and shoulders above all other science writers, is the fact that he’s on the ground in the middle of all the action. He’s tramping in the African jungle looking for gorillas, trying to avoid Ebola. He’s in Bangladesh helping to capture fruit bats for Nipah virus research, trying to avoid infectious airborne batsh*t. He’s eating bamboo rats in southern China, trying to avoid the SARS coronavirus. Intrepid is one word, but maybe crazy is more accurate. But it’s all to the reader’s benefit and had me flipping the pages quickly.

There’s a lot that can be said about an important topic like the next global epidemic, but allow me two brief comments. First, there are hundreds of people

who quietly risk their lives working in labs every day or flying to the other side of the world at a moment’s notice in order to prevent or contain these outbreaks. This book appropriately emphasizes how courageous they are and how important they will continue to be in protecting the future of the human race. There’s no way they get enough appreciation. Second, frequent scoffing is often heard when it’s publicized that our beloved tax dollars are spent exploring the intimate life details of an unassuming animal like the white-tailed antelope ground squirrel or the banded palm civet. What the critics don’t understand and what this book makes abundantly clear is that when the next epidemic hits, detailed knowledge of some unknown mouse, bat, goose, flea or other such creature may be immediately essential to prevent a global disaster. Our only defense against future scourges is knowledge of the natural world and we ignore that truth at our peril.

In the end, Spillover is an incredible book by a journalist who seems to be only getting better with age. It’s terrifying at times and guaranteed to occasionally give you the creeps, but it’s strongly recommended for anyone interested in this increasingly worrisome biological issue.

— D. Driftless

Monkey image by Muhammad Mahdi Karim.

- Best Non-Fiction of 2016 - February 1, 2017

- Little Free Library Series — Savannah - May 22, 2015

- Little Free Library Series — Wyoming - November 30, 2014

Leave A Comment