Important Topic, Lackluster Delivery

Important Topic, Lackluster Delivery

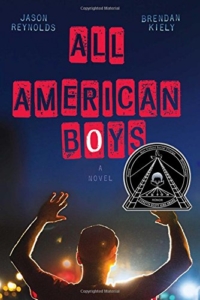

Authors: Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely

Recipient of multiple awards for children’s fiction and already mandatory reading in some Maryland schools, All American Boys was also chosen as the Frederick Reads title and therefore added as my book club’s October selection. Responding to a world in political turmoil, the dual authored All American Boys is more famous for its conversation starting capabilities than its plot. Examining the Black Lives Matter movement from all sides, the book is divided between two teenage boys. We have Rashad, a black boy who despite his questioning and love of what his father claims are hooligan clothes is a rock of the community and a straight-laced ROTC member. Immersed in a world where high school is the end-all and be-all and everything is about all things party, Rashad’s perspective violently shifts when he is randomly brutalized by a white policeman. The crime: supposed shoplifting. The evidence: non-existent. The situation: ridiculous.

Absent from high school, bones patching back together in the hospital, Rashad transitions from boy to man and watches, dumbfounded, as the nation spirals his case into a bigger discussion. Faced with the decisions of a world more complicated than friends, pretty girls, and parties, Rashad is thwarted by his own policeman father who despite being African American has some dark cop history and is essentially brainwashed by the same stereotyping that lead to the attack on Rashad.

Alongside Rashad’s painful journey, varsity basketball player and high school super star Quinn Collins is also emerging into a more complicated moral world. Being definitely in the wrong place at the wrong time, Quinn’s sports-centric world and bright future dreams of college and basketball scholarships are shattered by the harsh reality of watching his father figure and best friend’s brother, policeman Paul Galluzzo, brutalize a young boy in his own class – for nothing. Now Quinn must decide – does he really have the moral luxury to be silent? As the school around Quinn takes up the mantra of “Rashad is Absent Again Today” social media and the appearance of a video rattle not only the students, but the nation. Afraid of both conflict and personal sacrifice, Quinn’s “no dog in this hunt” mentality changes as the very widespread nature of the problem eventually breaks down his self-focus and leads to a terrifying set of decisions.

What’s interesting here is a book written for teens (and heck, anyone over 13 really) by a black and a white author, merging voices and perspectives. Indeed, the conversations that get invoked are certainly more profound and intentional than the text, which uses not so subtle rhetoric to support a position without ever bringing alive the world of Quinn and Rashad. Indeed, both boys are concepts and, once again, it’s the topic of the book and the conversation we can have as a community around it that carries the weight and the import. For the Frederick Reads title my library established a large session for the community to discuss this book and the issues within it. A young black man, recently graduated from college, was presented as a speaker to give the perspective on how black males are treated by the police specifically and society in general. Conversely, a white police officer volunteer was brought in to co-run this panel and answer the hard questions. The back and forth of the community and the two panelists was soon far away from the book (the book barely being mentioned) and deep into the concepts, both moral and political, and the root causes of corruption and prejudice. It was this lively discussion and the verve of the participants that I’ll remember – not that pseudo flimsy story that succeeds only because of what it makes us talk about.

When I was a pre-teen, we had Roll of Thunder Hear My Cry as required reading in school. Following the misadventures of a black family during the Depression era as they encounter prejudice and racism, Casey, the main character, was a real person to me and her strength, dignity, and resolve inspired me as a young woman and have lead me 10+ years later to remember the book and its message. Same thing for To Kill a Mockingbird, another piece about social morality that lives and breathes not only through the discourse it evokes, but the characters it presents. Can you really understand and summon the full support and sympathy toward your fellow man if you cannot imagine yourself in the same place? I don’t think so. And for me, that’s where All American Boys, despite its grandiose intentions and the way it keeps proudly stating that it examines all sides of a story, epically fails.

First off, despite the pretty even page space and chapters about the two boys, Rashad seems eerily absent from his own narrative. Quinn has the dilemma and if you have to select a “main character” he seems to be the one. Rashad, on the other hand, spends a lot of time in his hospital bed, ultimately just being. He’s quiet, a little afraid, mostly forgiving, and utterly alien to readers for a character under such extreme duress. At sixteen, or heck, any age, I’d predict a greater meltdown – decidedly more fear, confusion, and anger. Perhaps the very numbness that surrounds his chapters evinces a personal struggle so deep he cannot even come to terms with it. But this needed to be conveyed somehow – how his spirit died as averse to simple and strange apathy. He speaks, he has dialogue with his father, he has notably arduous teenage texting sessions with friends, and yet he seems like an idea, propped there to get us thinking without evoking the full humanity that this particular topic just demands.

Meanwhile Quinn, the white character, gets all the page space. His dilemma of determining to stand with his school friends against police brutality and racism seems to have greater weight and get more emotional oomph than Rashad’s story. Evidently this isn’t intentional, but equal pages don’t give equality to the characters and this soon becomes a call to arms for white audiences who think that they are outside of this topic, that it doesn’t affect them, and that doing nothing is acceptable. Diminishing the black character, however, and sidelining what should be extreme and borderline PTSD to focus on Quinn’s call to action seems like a tactical error or at the very least, lack of coordination between the two authors.

Quinn himself, while presented with a slightly more interior lens than Rashad, is equally distant. He is consumed with horror at what he witnessed, a strange desire to justify it and just be done with the whole horror, and a stifled conscious screaming for attention. His internal dilemma lets us be a bit closer to him, yet it’s still not taken far enough. Things are oversimplified, other teenage characters given the gift of useful eloquence at appropriate plot points, and the entire father angle discarded.

Paul Galluzzo, the police officer who assaulted Rashad and who is Quinn’s father figure, supposedly has a voice in the narrative, except he actually doesn’t. He’s really not even important and as a villain is completely static. He’s generic. He could be anyone or no one even. Quinn accepts the horror of Paul’s actions and begins to change his prospective based on what he has seen. Yet . . . this man also raised him. Quinn never felt the need to question Paul, to ask why he did what he did, how things went so bad. This seems like an elemental human need – confronting those we love when we see them engage in uncharacteristic and especially inhuman behavior. Yet Quinn is strangely able to let go of his surrogate father without even a single conversation. This should be harder, slower, and infinitely more complex.

In the end, everything comes to a head. Quinn and Rashad both have realizations, the school raises a dramatic event, everyone has some soul searching followed by a glorious internal transformation, and the community is geared up to take sides and stand up for what is right . . . leading to the ultimate ending, where nothing is resolved and the narrative stutters to an end like a wheezing old car. We never get any answers and while this was evidently done by the authors as an intentional way of having the readers decide how to historically write that final chapter . . . it just comes off on the page as sloppy. We don’t see the outcome, merely a “lie-in” protest. The characters may have had personal revelations, which are mostly distant and conceptual to us, but nothing changes or is even evident that it will change. Neither is there bitterness. Everyone is happily ever after yet we don’t know what happens to Paul Galluzzo or how the case plays out in court, if it even makes it this far. Instead, readers have trailed through a lot of filler pages focusing on a key conversation hidden in the murk of sloppy writing. All American Boys is glorified only because of its prescient topic which elicits, however inadequately, a needful discussion. There are so many other books out there, however, that take the topic all the way, that open discussions and examine human emotions, actions, and reactions, both monstrous and courageous, and remain in the reader’s mind and in social dialogue longer. All American Boys stands on the shoulders of these giants and it’s only getting attention, in my opinion, because this is a topic we need to talk about anyway and not because of how the book deals with it (or doesn’t as the case is). Right time, right place, inadequate story that nevertheless works as a much needed conversation starter . . .

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews/

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019