A life of loss…

Author: Zora Neale Hurston

Eye-witness testimony. It can be uniquely potent stuff, particularly when it involves mankind’s sordid tradition of slavery. It’s been more than 150 years since the last African slave ship arrived on the shores of United States of America. Almost 70 years later, a young woman named Zora Neale Hurston – who would go on to become an acclaimed novelist – spoke to the last surviving slave on that ship, often transcribing much of his story word for word. Notably, almost another century passed before the man’s story was finally published in 2018, revealing the kind of eye-witness testimony that was rarely collected from slavery survivors. Barracoon is that remarkable story.

Eye-witness testimony. It can be uniquely potent stuff, particularly when it involves mankind’s sordid tradition of slavery. It’s been more than 150 years since the last African slave ship arrived on the shores of United States of America. Almost 70 years later, a young woman named Zora Neale Hurston – who would go on to become an acclaimed novelist – spoke to the last surviving slave on that ship, often transcribing much of his story word for word. Notably, almost another century passed before the man’s story was finally published in 2018, revealing the kind of eye-witness testimony that was rarely collected from slavery survivors. Barracoon is that remarkable story.

It was 1860 and despite the fact that the trans-Atlantic slave trade had been banned for more than fifty years, there was still a market for new slaves. As they’d been doing for centuries, warriors from the Kingdom of Dahomey (in present day Benin) captured a young man named Oluale Kossola during their spring slave raids in what is now part of Nigeria. Marched overland to the ocean with many of his fellow villagers, he was locked up in a barracoon or slave pen near the shore and eventually sold to the owner of the illegal slave trader Clotilde. The ship managed to evade the slave trade blockade enforced by the British Royal Navy and landed in Mobile, Alabama with Kossola and 109 other Africans on board. It was here that the young man was given a new name, Cudjo Lewis, that he was to use for the rest of his life.

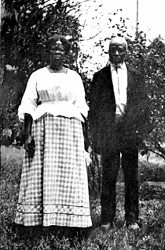

Despite his advanced age, Cudjo tells his story to Hurston with vivid clarity, passionately expressing a deep longing for his homeland many decades after was taken from Africa. He goes on to tell of his experience following the Civil War, when he was suddenly freed, but had no resources available to allow him to support himself. Hurston captures the bittersweet reminiscences of the man by just letting him tell his story in his own distinctive – and often quietly powerful – way. She also reveals his pride when he tells of how, along with some of his fellow Clotilde slaves, he went on to found Africatown, now a historic neighborhood in Mobile.

Cudjo’s story is intriguing simply as a unique biography, but it also sheds light on some of the complexities that surrounded slavery. When Hurston interviewed him, the conventional narrative of the slave trade was simple; evil white Europeans captured innocent black Africans and shipped them across the ocean. The essential role that other Africans played in raiding inland villages to round up new slaves had not been recognized. This new information impacted black intellectuals like Hurston, upsetting and complicating their idealized view of their African homeland. Cudjo’s testimony also sheds some less than flattering light on human nature as well. Still bitter and resentful, he recounts how the American-born slaves he encountered in Alabama frequently ridiculed the strange languages and customs of the newly arrived – and profoundly traumatized – native Africans with whom they shared their lot.

In addition, the book provides an interesting look at the early life of Zora Neale Hurston. A notable participant in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, which fostered a new respect for African cultural heritage, she would go on to receive great acclaim for her subsequent works, most of it after her death in 1960. Commentary by Hurston biographer Deborah G. Plant and novelist Alice Walker is included in the book, providing some helpful back story.

Lastly, even the book’s publication story is interesting. When Hurston first wrote the work, publishers refused to accept her depiction of Cudjo’s sometimes challenging dialect. She was unwilling to compromise on this issue and the book never went to press. The fact that it took almost 90 years to finally be published is difficult to believe, but it’s hard to imagine the story being told any other way.

Spanning the centuries and long overdue, Barracoon gives voice to the kind of African American narrative that has rarely been heard. Thanks to young Hurston’s wisdom, patience and persistence, Cudjo Lewis’ incredible story resonates powerfully, even in the 21st century. Highly recommended.

— D. Driftless

Lewis photo by Emma Roche/ cemetery photo by Leigh T. Harrell (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Check out some of Dave’s other reviews of books about slavery in the US: Twelve Years a Slave / The Wanderer / The Half Has Never Been Told

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”0062748203″]

- Best Non-Fiction of 2016 - February 1, 2017

- Little Free Library Series — Savannah - May 22, 2015

- Little Free Library Series — Wyoming - November 30, 2014