If Monty Python Dealt With Race. . .

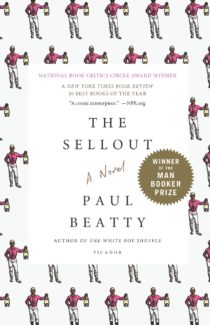

Author: Paul Beatty

Following on the heels of the disturbing bestseller Underground Railroad which used magical realism to capture decades of slavery and racism in America, my book club selected The Sellout, a twisted “satire” of modern day America and the invasive and everlasting nature of racial definitions and stereotypes. The Sell-Out is the first book by an American author to win the Man Booker Prize (which it won in 2016) and has been on everyone’s radar and the bestseller list since, breeding a whole host of confused reviews which nervously laugh along with Beatty while at the same time being distinctly, obviously uncomfortable with both the man and his work which defies expectation and loose terms like “satire” and “comedy.”

The story is essentially Monty Python if the clever creators were black and wanted to deal with race. The absurdity is both outlandish and vicious, starting in a California ghetto called “Dickens” where life is defined by what gang you belong to (evident Crip sympathies abound) and your status at the Dum Dum Donuts Intellectuals meeting. Bonbon, our unnamed narrator called only by his nickname and then only by his on-again-off-again sweetie, is the result of a sociologist father determined to make him into a black Einstein with acute racial awareness and the balls to do something about the plight of African Americans. Instead, Bonbon’s father ends up shot by the police and now the narrator is on his own with all his confusion and his consummate capability of just not giving a fuck about anything (perhaps the result of all that electro shock treatment thanks to his mad-scientist wannabe daddy). What Bonbon does have the guts to do – if only out of confusion and for the desire of desecrating the memories of the dead – is reinstate slavery and segregation in Dickens to get the township back “on the map.” What follows in an absurdist trip down a dark alley with a character whose father issues eventually evolve into what they always were – an overall cultural identity crises.

Bonbon is the quintessential cynical and lost-at-heart character. With a piece of agricultural land in the middle of the ghetto and the ability to grow both fine watermelons and weed, Bonbon’s life is mostly defined by what’s missing – and that big Supreme Court case he causes to occur during the prologue. Dealing with the fallout of what can only be described as a weird father/son relationship, Bonbon suddenly finds the “clever old man” figure – but not in the way you at all expect. Hominy Jenkins, last surviving Little Rascal, who’s career is mostly on the cutting room floor, takes a liking to Bonbon and becomes his slave. Bonbon is then advocated to beat the old man in an absolutely cringeworthy scene (he later takes him to BDSM hookers paid specifically to administer the master’s punishment) while placing him in roles of stereotypical servitude from living lawn jockey to human footstool and every other demeaning role in-between.

With a slave in tow, being the devil in his ear, old-man Hominy reliving his glory days as a performing “cultural icon” joke, the easy-come-easy-go Bonbon drifts into an entirely different trouble. To make the old man happy, he brings back segregation – first on the Dickens’ bus and later in the Dickens’ middle school. In this mostly African American community (where the Hispanics are seen as the enemies), the restless population surprises readers (although really, we should have seen it coming) by being gung-ho to reinstate traditional American legacy. After all, school segregation has finally heightened Dicken’s waning grades and it just might be that this is the final straw that will get our beleaguered little community on the map.

What’s especially interesting about The Sellout is that while everyone is claiming “satire!” and “comedy!” Paul Beatty himself denies the definition of his book and doesn’t consider himself a satirist or think his book is funny – check out The Paris Review for a breakdown of his comments. Instead, Beatty feels that talking about the funny portions of the book is a way to avoid how damned uncomfortable the entire read makes us as readers from the unrelenting “N” word to the fact that Bonbon will always “go there” and say just about anything to anybody as readers stare on slack jawed. As a white reader it’s not a comfortable book to read and you just can’t help thinking “can they really say that,” “can this really be published,” “what on earth am I going to say in book club,” and etc. As a black reader, I’m not sure what the perception would be – but I’m betting it’s still uncomfortable. And that’s kind of the entire point which so many reviews and write-ups seem to be missing. It’s funny in that “I’m laughing because I’m too shocked to say anything you-cannot-be serious way.” Satire? Not really. Vicious take-no-prisoners rage fueled by an intuitive sense of irony and the strangely awful beauty of tragedy – yes, that’s more like it.

What does the book mean? I really can’t definitively say and it makes me feel dumb to admit it. I have my interpretation of the surrealistic conclusion and what it all means, but no two reviews out there from the practically cringing New York Times to the Amazon blurb seem to be able to say either. It’s just “funny,” and “satire,” and “over-the-top,” and “provoking,” even “profane,” but no one can summarize what all of that combines together to really mean. The Sellout, at least to me, is the portrait of a cracked mirror. Society, which claims to be living in a post-racial world (I’m generalizing, deal with it) is anything but and while we’re not comfortable with admitting this, in our darkest moments when everything falls behind, we even find comfort in going back to the derogatory “old days” because at least it is some way to acknowledge the elephant in the room – a defined albeit horrible standard to act out and speak to. Bonbon is ultimately uncomfortable because he doesn’t know how to talk about race in his (our) world, and his acting out is a way to search for identity and re-live everything before him that has gone together to create this mix-matched portrait we have of the American black person or persona. In the end, he realizes how he’s sold everything (read, everybody) out. He comes to understand that his experiences that were basically defined before his own birth, for generations back, have come together to craft a complex identity that despite the discomfort cannot be escaped. And it’s here the book ends on anything but a humorous note. If I had to select one word to describe The Sellout that word would be rage.

And it’s here that the book lost me somewhat. I get the message, even appreciate the symbolic way it was delivered and how Beatty uses extremism to hit the readers between the eyes – yet I’m not sure I totally buy it. The rage, somehow, is too visceral without being real, sort of a depression fueled mania that twists in on itself but doesn’t offer any answers or solutions. Are things really this bad? No doubt society is prejudiced and this has left a mark on all Americans – but this completely unfixable? Perhaps so, yet the very method of delivery, this absurdist all-the-way hyperbole, the “satire” the critics speak of distanced me so far from the actual world and the obviously stereotypical characters, that fact all bled into fiction until I had nothing to believe and no “real” experience or emotion to act as a call to action. This cry is often my “issue” with books in that to feel I don’t want intellectualism, no matter how cleverly disguised by technique (as Beatty has undoubtedly done) but the personalized touch of a narrator who takes me out of my world and puts me into his own. I never felt alongside Bonbon and eventually the very tropes that make this book such interesting literature also hindered its message because by the conclusion, I was tired of the amplified absurdity and the self-indulgent rage and instead wanted a feeling less literary and more “everyman.” I want to feel, and by feel I need something more than dissolute anger hiding behind cleverly turned craft.

– Frances Carden

Follow my reviews on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/xombie_mistress

Follow my reviews on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/FrancesReviews/

[AMAZONPRODUCTS asin=”1250083257″]

- Book Vs Movie: The Shining - April 6, 2020

- Thankful For Great Cozy Mysteries - December 13, 2019

- Cozy Mysteries for a Perfect Fall - October 20, 2019