Final Photos…

Author: Erroll Fuller

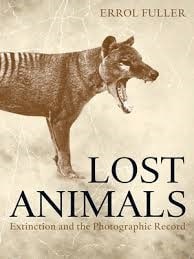

A blood thirsty carnivore may not be the first creature that comes to mind when you hear the word “marsupial”. But that’s because you’ve never seen a thylacine. More tenacious than a peaceful cud-chewing kangaroo or a dopey eucalyptus-hugging koala, the thylacine was the largest marsupial carnivore known in modern times. Also called the Tasmanian tiger, but more closely resembling a wolf, the thylacine’s territory was limited to the large island of Tasmania when Europeans first arrived down under. Unfortunately, settlers’ sheep and chickens proved irresistible to the predator and retribution was swift and complete, leading to the government sanctioned slaughter of the last wild thylacine in 1930. As the environmental movement has grown since then, this enigmatic animal has become a poster creature for the tragedy of human-caused extinction. A case in point is the photo of a thylacine – alligator-like toothy jaws gaping wide – on the cover of Errol Fuller’s haunting collection of obituaries, entitled Lost Animals.

A blood thirsty carnivore may not be the first creature that comes to mind when you hear the word “marsupial”. But that’s because you’ve never seen a thylacine. More tenacious than a peaceful cud-chewing kangaroo or a dopey eucalyptus-hugging koala, the thylacine was the largest marsupial carnivore known in modern times. Also called the Tasmanian tiger, but more closely resembling a wolf, the thylacine’s territory was limited to the large island of Tasmania when Europeans first arrived down under. Unfortunately, settlers’ sheep and chickens proved irresistible to the predator and retribution was swift and complete, leading to the government sanctioned slaughter of the last wild thylacine in 1930. As the environmental movement has grown since then, this enigmatic animal has become a poster creature for the tragedy of human-caused extinction. A case in point is the photo of a thylacine – alligator-like toothy jaws gaping wide – on the cover of Errol Fuller’s haunting collection of obituaries, entitled Lost Animals.

While the thylacine is no more, there are a few photographs in existence and Fuller, a British author and artist, has collected these mementos along with images of 27 other extinct birds and mammals in this unique book of elegiac photography. Scouring archives high and low, publishing some pictures for the first time, the author has unearthed some undeniably poignant portraits, a few of them depicting the last known member of their species. Including well-known animals, like the passenger pigeon and the ivory-billed woodpecker, as well as creatures you may have never heard of, like the laughing owl and Schomburgk’s deer, Fuller displays the few existing pictures and movingly tells of the animals’ final days.

Many of these species became extinct just as the age of photography was dawning, meaning that some of the images couldn’t be more fleeting or vestigial, much like the animals themselves. As anyone who’s tried knows, it’s hard to take a good picture of an animal – particularly in the wild with primitive equipment – so the fact that anyone ever captured an imperial woodpecker or a New Zealand bush wren on film is entirely remarkable. Fuller’s account of the photographic hurdles overcome to create these images adds an additional interesting side story to the book.

While each notable photograph conveys a poignant sense of loss on its own, Fuller’s accompanying prose delivers a thoughtful and illuminating epitaph for each species. Providing plenty of natural history information, as well as details about the species’ final days, Fuller deftly balances the cold hard facts with the inevitable emotions.

A unique photographic history of extinction, Lost Animals provides somber testimony to humankind’s ongoing legacy of ecologic ruin. The fact that these few images, often of marginal quality, are all that remain of these remarkable creatures is sure to cause heartache for many readers. Hopefully, this poignant memorial can serve as a motivating force, helping to keep other fascinating animals from joining the ever growing list of the lost. Highly recommended.

— D. Driftless

Parakeet photo by James St. John / Thylacine photo by E.J. Keller

Other Readers Lane reviews about extinction:

- Best Non-Fiction of 2016 - February 1, 2017

- Little Free Library Series — Savannah - May 22, 2015

- Little Free Library Series — Wyoming - November 30, 2014

Leave A Comment